Review Article

A Review of Chewing Movements of Young Individuals According to the Gender During Orthodontic Treatment

Bilgin Giray1 and Serdar Gözler2*

1Department of Orthodontics, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey

2TMD Clinic of Prosthodontic Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey

*Corresponding author: Serdar Gözler, TMD Clinic in Prosthodontic Department, Faculty of Dentistry, Istanbul Aydiin University, Istanbul, Turkey, Tel: +90 2122919292; Fax: +90 2122307593; E-mail: serdargozler@aydin.edu.tr

Citation: Giray B, Gözler S (2017) A Review of Chewing Movements of Young Individuals According to the Gender During Orthodontic Treatment. J Dent Sci Res Ther 2017: 17-25. doi: https://doi.org/10.29199/2637-7055/DSRT.101011

Received: 26 June 2017; Accepted: 27 September 2017; Published: 12 October 2017

Abstract

The aim of the present research was to evaluate and compare distribution of chewing movements of the young individuals with normal occlusion and malocclusion according to the male and female gender and to compare the movements. Furthermore, examination of whether a difference exists on chewing movements according to the gender was also addressed.

Materials and methods: This is a prospective clinical study carried out on totally 63 individuals including 43 patients with malocclusion and an age average of 16.79 years whose growth and development terminated partially and 20 individuals with normal occlusion and age average of 24.77 years who did not have any orthodontic treatment. Totally 63 individuals including 25 individuals with skeletal and dental Angle Class I, 18 individuals with skeletal and dental Angle Class II before and at sixth month of the orthodontic treatment and 20 individuals as the Control group were enrolled into the research. The gender difference of totally 17 males including 8 Class I males and 9 Class II males and 26 females including 17 Class I females and 9 Class II females with normal occlusion were evaluated. Finally, association between 17 Class I and Class II males and 26 females were checked. Chewing movements obtained through a Jaw Tracker were used in the present study. Chewing Opening Time (msec), Chewing Closing Time (msec), Chewing Occlusion Time (msec), Total Chewing Time (msec), Vertical Chewing Length (mm), Chewing Opening Velocity (ms) and Chewing Closing Time (ms) were analysed. In consideration of equal number of samples (n=n1=n2) and states of different number of samples, paired sample t-test and Wilcoxon test were used to compare averages of two dependent groups whereas independent sample t-test and Mann Whitney U test were utilized for comparison of two independent groups.

Results: Although there was not any statistically significant difference detected between occlusion duration and total chewing cycle as well as average open velocity (mm/sec), statistically significant differences were found between opening, closing chewing velocities and average closing velocity (mm/sec) (P<0.01). For female patients, statistically significant results were obtained in distance between opening and closing and opening and closing velocities. Moreover, statistically significant difference was detected between closing of males and females at the onset of the treatment and at sixth month. It was detected that malocclusion has a statistical significance in chewing difference between the genders during initial treatment and other parameters were not important. A similar association was also found between changes at initial treatment and at month 6.

Conclusion: The present research was carried out to detect the distribution between the genders through comparison of the individuals with Class I and Class II abnormalities as well as the individuals with normal occlusion at the beginning of and during the treatment. However, there was not any association detected in terms of the parameters between girls and boys with Class I and Class II abnormalities along progress of the treatment.

Keywords: Class I and Class II; Jaw Tracker; Mastication; Occlusion; Orthodontic Treatment

Introduction

Age and gender are quite important for orthodontic treatment planning. Differences in growth and development of the individual according to the gender should always be considered. Therefore, evaluation of chewing performance according to the genders should be taken into account to achieve an efficient occlusion. The aim of the present research was to examine distribution of Class I and Class II malocclusions and the association between the genders. A Jaw Tracker device was needed to be able to analyse the changes before and after the treatment. There are limited number of studies searching the differences in chewing movements between the genders [1]. A study conducted by Julien et al., [2] measured and compared chewing performances of 47 healthy young adults (15 males, 15 females, 15 girls and 2 boys). Occlusion, temporomandibular joint function, skeletal classification and dental statuses were evaluated as determinative criteria. Another dimorphism study performed by Toro A et al., [3] compared chewing efficiencies of 335 children with age averages of 6, 9, 12 and 15 years and detected that chewing efficiency changes according to the age and a better chewing performance appears by aging. A similar study conducted by Braun S et al., [4] tested bilateral maximum biting strengths of 231 males and 236 females and found a biting strength of 176 Newton at 18-20 years of age, 78 Newton at 6 and 8 years of age. Biting strength increased by aging. The previous studies suggested that adult males have a stronger biting strength than females. However, such difference is not significant during growth and development. The biting strength difference related to the gender probably increases after puberty by development of muscle mass in males [4].

Okeson JP [5] suggested that aesthetic is an important factor for orthodontists; however, it should be remembered that chewing functions and orthopaedic principles should be considered. Orthopaedic stability in chewing structures should focus on reducing the risk factors associated with developing temporomandibular disorders. Awareness of occlusion is important for treatment, because, occlusion would affect chewing functions of each patient lifetime. Hill L [6] reported that chewing cycle has three main phases. These are; Opening Time-OT, Closing Time-CT and Occlusal Time-OcT. A normal chewing cycle varies between 600 and 900 milliseconds and each phase is roughly 1/3 of total chewing cycle. The occlusal time only is slightly less than 1/3 of total cycle. Chewing movements are recorded at three planes including frontal, sagittal and horizontal. The conversion moment of opening phase to closing phase is called Turning Point (TP) and the level where occlusion phase stops is called Terminal Chewing Position. Although it is called as occlusal phase, teeth may not have contact with each other at terminal chewing position. Distance of the teeth with each other is about 0.3mm +/- 0,1 mm at this phase [6]. A similar study which included Opening Phase, Closing Phase and Occlusal Phase as parameters detected opening and closing phases as 225 +/- 25 msec and occlusal phase as 200 +/- 25 msec [7].

A study conducted by Kayukawa H [8] addressed that some dynamic myofunctional treatment types should be included into orthodontic treatment planning along with correction of static and structural abnormalities. However, Leite et al., [9] reported outcomes of a study conducted about orthodontic treatment and malocclusion for 15 years and suggested that temporomandibular joint disorder does not appear in the patients who had orthodontic treatment. Even long-term studies revealed that protective orthodontic or different treatment options prevent development of temporomandibular joint disorders. However, it was also emphasized that these studies should be continued. The association between occlusal changes and temporomandibular disorders was compared in a prospective study carried out by Henrikson et al., [10,11] through use of EMG and 58 girls with Class II malocclusion were compared with 65 treated girls. Age average of the individuals in the research group was 12.07. There was not any change detected in mouth opening closing distance, lateral occlusion and protrusion in mandibular movement between the groups Mouth opening=53 mm). Mouth opening has become 54 mm two years later. In the foresaid study, the food bite with a hard consistency creates the chewing pattern at frontal plane with a smaller closing angle as well as a higher peak velocity. The decrease in prevalence of muscular symptoms in TM disorders is different than the group with normal occlusion. They associated this with a decrease in muscle hyperactivity because of mobile or sensitive teeth during orthodontic treatment. Similarly, Eger mark et al., [12] reviewed clinical findings of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) of girls and boys in 50 patients (age average of 12.9 years) before, during and just after the orthodontic treatment. We considered to search the subject to enlighten orthodontic treatments and to contribute to the literature since there is not any kind of study recently. The aim of the present study was to compare chewing patterns of the individuals with skeletally normal occlusion and those with abnormalities in boys and girls. This comparison includes chewing efficiency, opening and closing times, occlusal time during chewing, vertical opening distance and the distance at the moment from end of the opening and start of the closing in both groups and between the genders.

Material and Methods

The present prospective clinical study was carried out on 63 individuals referred to Orthodontics Department of Dentistry Faculty of Istanbul Aydin University for treatment purposes in 2016 including 43 patients with malocclusion and age average of 16.8 years whose growth and development terminated partially including 17 males (39.5%) and 26 females (60.5%) and 20 individuals with normal occlusion and age average of 24.8 years who never had any orthodontic treatment before. Healthy individuals who were at permanent dentition period and might tolerate the treatment were also included into the study.

The participants were divided into three groups; Group I included 25 individuals (8 males and 17 females) (58%); Group II included 18 individuals (9 Males and 9 Females) (41.9%) and Group III included 20 untreated individuals (10 Females and 10 Males) with normal occlusion as the control group. Data collection was performed with the parameters created from three main components during chewing at two intervals; T0 Before the treatment and T1 sixth month of the treatment. Fixed edgewise Roth technique was applied to all patients. During first six-month period of the treatment, 0.22 inch Roth bracket and 0.014 Ni-Ti arch wires for alignment of lower and upper mandible at the beginning were used; 0.016, 0,018 and 0.016 x 0.022 Ni-Ti arch wires were used during the treatment.

Inclusion Criteria

The individuals were enrolled in consideration of the following criteria; being at the end of pubertal excretion period skeletally; individuals being at permanent dentition period and eruption of all teeth; being Angle Class I and Class II in terms of skeletal and dental molar association clinically and not having premolar and molar tooth loss more than one and for the control group, having skeletal and dental molar and canine teeth with normal occlusion and Angle Class I and minimum crowding on the anterior zone.

Exclusion Criteria are as Follows

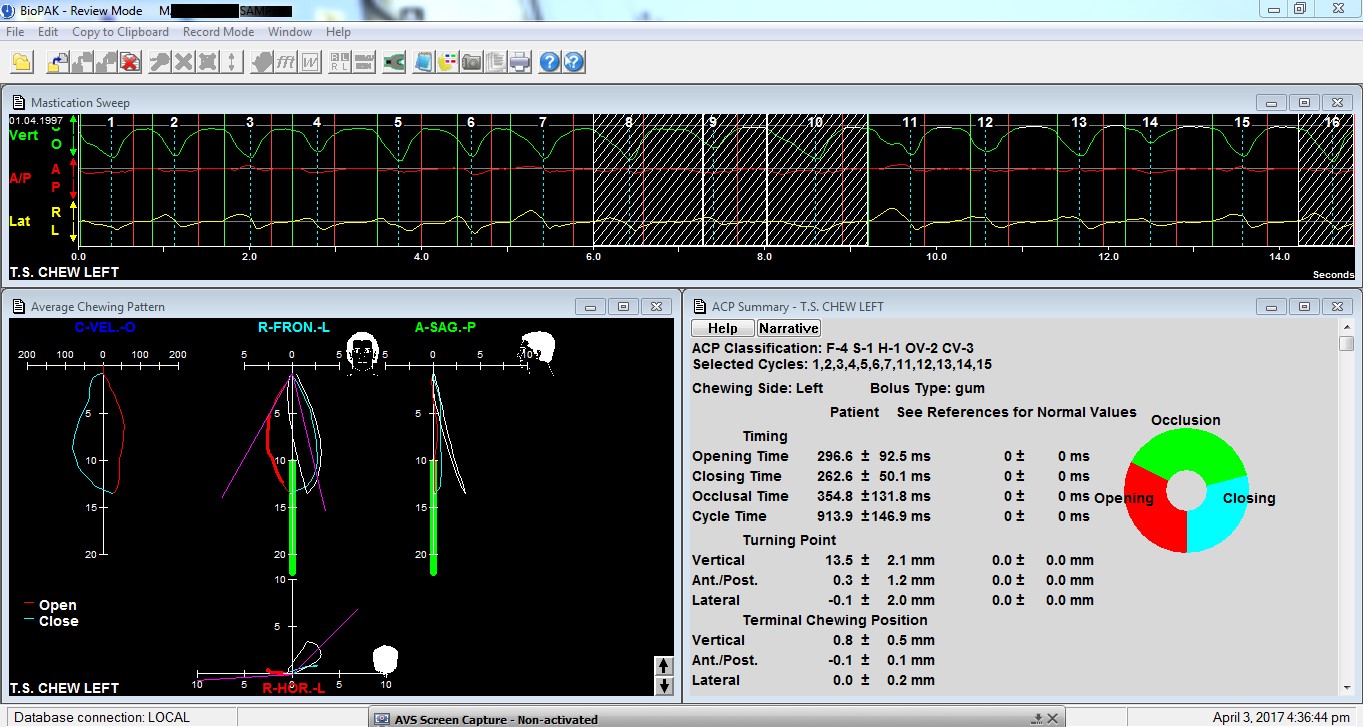

Individuals with previously known syndrome, systemic disorder, craniofacial abnormality, cleft lip/palate; individuals who had any orthodontic treatment before with removable or fixed apparatus; individuals with complaint of any periodontal and temporomandibular joint disorder and congenital tooth deficiency except 3rd large grinders. Approval of Istanbul Aydin University, Medicine and Health Sciences Research Board and Committee of Ethics were obtained to carry out the research (B.30.2.AYD.0.00.00-480.2/0106, ANNEX-1). All individuals participated into the present research voluntarily and informed consent forms were obtained from all patients and their parents (ANNEX-2). The study materials consisted of lateral cephalometric and panoramic radiographs taken before and during fixed orthodontic treatment with/without exodontia, intraoral and extra oral digital photos, orthodontic cast models and Chewing Analysis records (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: Evaluation of chewing patterns with JT. Opening, closing, occlusal and cycle times were provided in msec. Vertical opening was measured in mm and the intervals at turning points and the distances at terminal chewing position were provided mm/msec. |

Lateral cephalometric films of all participants were taken in Orthodontics Department of Istanbul Aydin University. The anatomic spots and measurements used in the present research were obtained through selection from Steiner analyses. Ten lateral films were selected randomly and radiographs of same patients were drawn subsequently with one-month interval to minimize the errors of drawing. Method error of each measurement was calculated to detect repeatability. Measurement recurrence coefficients range between 0.95 and 0.99. For the cephalometric spots, planes and angles used in the research; spot S was marked as cella; Spot N was marked as frontonasal suture. Evaluation of lateral cephalometric films; films with angle ANB between >0° and <4° with crowding at lower and upper mandibles were selected as Angle Class I malocclusion group; films with angle ANB >4° was evaluated as skeletal Angle Class II Div1 and selected as Class II malocclusion group; films with angle ANB between >0° and -<4° and individuals with normal occlusion who do not need any treatment were selected as the control group. The association of chewing movements with occlusion and characteristics of chewing pattern of the present study were obtained by a device called Bio-JT developed by Bioresearch Inc. (USA) and a chewing analysis software developed by Prof. Maruyama [13,14].

For occlusion evaluation of chewing movements in the study, head of the patient was positioned to make the Frankfort plane parallel to the ground. The head part was placed to the patient for chewing movement and both sides were made symmetrical and even through right and left screws. The lower horizontal bar was placed; then, a special magnet adhesive which was specifically developed for the device was placed on anterior surface of lower-anterior teeth through a wax (Ormco, No.757-0001) and fixed. A gum was given to the participant and the participant was instructed to chew it on the left side. Same chewing movement was instructed to all participants both in the control and study group and uniformity of the study was provided. After a chewing movement for about 15 to 20 minutes, record was completed and the procedure was ended; the records were kept in the computer for statistical analysis. Analyses of the present study was performed on 7 parameters obtained through three main components during chewing: 1. Opening Phase, 2. Closing Phase, 3. Occlusal Phase and cycle T millisecond (msec). Turning point vertical was measured as mm whereas average opening/closing velocity were measured in mm/msec. The data includes chewing efficiency of the individuals without abnormality and the individuals with malocclusion.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical evaluation performed with the findings of chewing analysis: Power and Sample Size Calculation (Version: 3. 1. 2, Copyright 2017, Informer Technologies, Inc. USA) software was used for selection of the individuals and creation of the groups. Although working with equal sample sizes are highly desired, the present study was carried out on the groups with equal unit sample counts and different unit sample counts. The study was started with 90 individuals and this sample count was reduced to 63 by considering the inclusion criteria. The strength of the test was accepted as 80% and significance level as (P<0.05) for hypotheses to be established on at least 13 patients (13 and 43 patients each in both groups) through sample calculation program [15].

All statistical analyses performed on the database were done through SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics Version 19-22, USA). Averages and Standard deviations of all samples were calculated by this software. In consideration of equal sample counts (n=n1=n2) and different sample counts, paired sample t test was used for comparison of averages of two dependent group averages. Furthermore, the Wilcoxon test which is a non-parametric test was used (since the mass distribution where the samples were selected was considered to be small). “Independent sample t test” and Mann Whitney U test were utilized for comparison of two independent group averages. The P values of (P<0.05) and (P<0.01) were accepted as significant, respectively for the hypotheses to compare the differences between averages of the variables in both groups [15].

Results

The findings of the present study were reviewed in four sections. In section one; averages of the variables of 17 young individuals including 8 males with Class I abnormality, 9 Males with Class II abnormality as well as 10 adults as the control group and statistical differences were checked for significance detection (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Averages and significance control of the variables in males in the malocclusion group before the treatment T0 when compared with the control group (p<0.05) *, (p<0.01) ** (NS), Not Significant. |

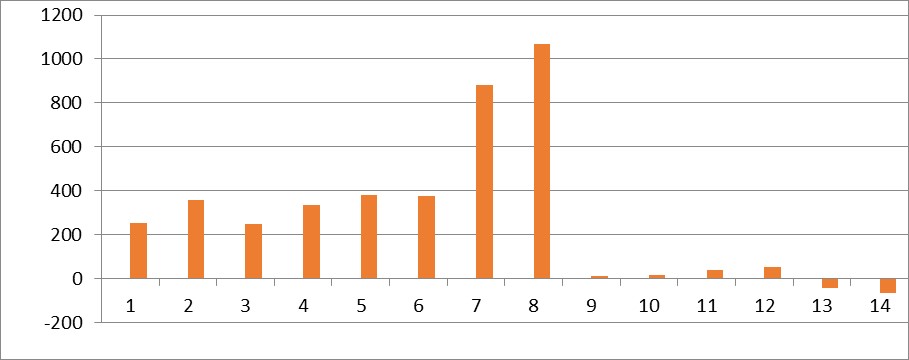

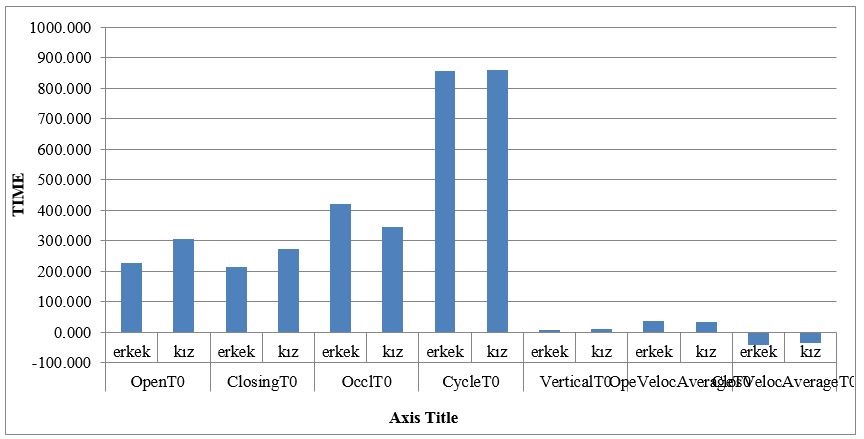

As a result of comparison of Class I and Class II malocclusion group with the control group in terms of seven parameters; it was concluded that OcclT0, CycleT0 and average opening velocity T0 variables of the control group were lower and average opening velocity variable of the control group is higher; however, such increase was not statistically significant. OpenT0, ClosingT0, VerticalT0 and Close Velo, averageT0 parameters of the control group are higher with statistically significant changes (P<0.01). Distribution of Class I and Class II malocclusion in males when compared with the control group was presented in (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2: Averages of the variables in males in the malocclusion group and the control group before the treatment T0. |

In section two; significance control of 26 girls including 17 girls with Class I malocclusion and 9 girls with Class II malocclusion as well as 10 girls of the control group and of the statistical difference appeared as a result of difference detection were performed (Table 2).

|

Table 2: Averages and significance control of the variables of the girls in the malocclusion group before the treatment when compared with the control group T1 (p<0.05)*, (p<0.01)** (NS) Not Sig. |

Although OpenT0, ClosingT0 variables of the control group were higher than the malocclusion group; and OcclT0, CycleT0 variables of the control group is lower than malocclusion group, such difference was not statistically significant. Vertical T0, Open velo, AvaregeT0 and Close veloaverageT0 (P<0.01) were found statistically significant. Distribution of such variables was presented in (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3: Averages of the variables in females in the malocclusion group and the control group before the treatment T0. |

Section three included statistical evaluation of the change in 8 boys and 17 girls with Class I malocclusion at sixth month and these evaluations were presented in (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Evaluation of the changes in males (8) and females (17) with class I malocclusion at onset of the treatment and at sixth month and the association between them. (p<0.05)*, (p<0.01)** (NS) Not Significant. Paired t test and Wilcoxon test. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

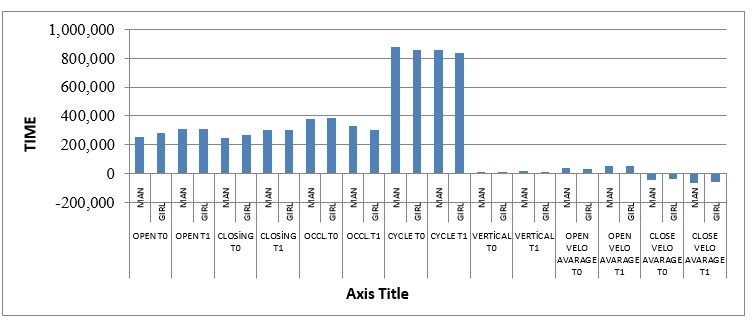

The changes of Open T0 (p< 0.01), Closing T0 (p<0.01) and Closing T1 (p<0.01) between the onset of the treatment and at month six were found statistically significant. The changes in other parameters were not statistically significant during the treatment. Averages observed are provided in (Figure 4).

|

Figure 4: Averages of the variables at onset of the treatment and during six-month period. |

In section four, statistical evaluations of 17 males with Class I malocclusion and 26 girls with Class II malocclusion at onset of the treatment and at sixth month are presented in (Table 4).

|

Table 4: Evaluation of the association between males and females with Class I and Class II malocclusion before and sixth month of the treatment. (p<0.05)*, (p<0.01)** (NS) Not Significant. Comparison of the averages between the groups. Mann Whitney U test was used. |

The changes between onset of the treatment and at sixth month were not significant. The averages observed are given in (Figure 5). The changes between the genders in Class II malocclusion group were not found statistically significant. No difference was detected between the genders

|

Figure 5: Averages of the variables at onset of the treatment and at month six. |

Discussion

The insignificant difference between occlusal time and total cycle time in the control group and the study group at the beginning of the study and contradiction of our outcomes with findings of Julien et al., [2] may be caused by the fact that our study and control group are below adult age and development of both groups still continue. Furthermore, there is a significant difference between opening, closing and mean chewing period values (P<0.01). Although the difference in occlusal time is not statistically significant, the difference between opening and closing velocities which requires a good coordination of chewing muscles and is the most important indicator of chewing efficiency indicates the effect of malocclusions on chewing efficiency. Such outcome was presented in table 1 and figure 1 in numeric and graphic values and the findings obtained are consistent with the study conducted by Toro et al. [3]. In the second section of the study, there are differences in the group which consists of 26 girls only including 17 girls with Class I and 9 girls with Class II malocclusions at the beginning of the study; however, such difference was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, since the difference in vertical time, opening time and mean and closing times were found significant at 0.01 level, this finding is consistent with the study conducted by Braun et al., [4]. Age increase is important to affect chewing performance. By increase of age, opening and closing velocities as well as the changes in associated parameters were detected at a significant level. However, in line with the study conducted by Braun et al., [4], the difference between girls and the boys was not significant during the period before puberty. This outcome is consistent with the results of the study conducted by Leite et al., [9]. Although a change appears in opening and closing velocities during the treatment, since there was not any difference in main formation of the chewing pattern may indicate that the individuals may adopt the changes appeared as a result of the treatment during their development period. The issue if possible changes would be significant for dimorphism when the treatment is performed during pregnancy should be investigated in another study [3].

Examination of males and females revealed significant values in parameter differences related to opening and closing velocities which shows the chewing efficiency. However, other differences were not statistically significant and this outcome shows that chewing patterns are rapidly and strongly monitored by periodontal receptors and a good adoption is achieved. Moreover, the adoption of muscle and nerve physiology in genders during the treatments performed at puberty should be searched individually. Nevertheless, the therapeutic changes in occlusion would be rapidly effective even though a disorder appears. Such outcome also complies with the findings obtained by Kerstein et al., [16]. The indicators for chewing performance which was obtained in the present study and found statistically significant in girls and the boys at sixth month of the treatment were statistically significant; and these should be discussed as another indicator for adoption of periodontal receptors which have an important role in coordination of chewing muscles especially during developmental period.

Conclusion

Significant differences were found in some values of chewing performance in comparison of boys and the girls with normal occlusion who were about to complete their development. This indicates the joint movement which is different between individuals with malocclusion and individuals with normal occlusion. Since the differences between other parameters were not found statistically significant, this may be explained by continuation of development of the boys. The difference in association of the treatment of Class I malocclusion and opening and closing times between the genders may suggest both development period and change of muscle function. We also find lack of correlation as normal in both malocclusion types between the genders. This kind of studies should be reviewed at the end of the study and after retention.

References

- Thomas GP, Throckmorton GS, Ellis E, Sinn DP (1995) The effects of orthodontic treatment on isometric bite forces and mandibular motion in patients before orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53: 673-678.

- Julien KC, Buschang PH, Throckmorton GS, Dechow PC (1996) Normal masticatory performance in young adults and children. Arch Oral Biol 41: 69-75.

- Toro A, Buschang PH, Throckmorton G, Roldán S (2005) Masticatory performance in children and adolescents with Class I and II malocclusions. Eur J Orthod 28: 112-119.

- Braun S, Hnat WP, Freudenthaler JW, Marcotte MR, Hönigle K, et al. (1996) A study of maximum bite force during growth and development. Angle Orthod 66: 261-264.

- Okeson JP (2015) Evolution of occlusion and temporomandibular disorder in orthodontics: Past, present, and future. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 147: 216-223.

- Hill L (2016) An Introduction to Mastication Analysis in General Practice. Oral Health Gorup, Canada.

- Kuwahara T, Miyauchi S, Maruyama T (1993) Clinical classification of the patterns of mandibular movements during mastication in subjects with TMJ disorders. Int J Prosthodont 5: 122-129.

- Kayukawa H (1992) Malocclusion and masticatory muscle activity: a comparison of four types of malocclusion. J Clin Pediatr Dent 16: 162-177.

- Leite RA, Rodrigues JF, Sakima MT, Sakima T (2013) Relationship between temporomandibular disorders and orthodontic treatment: a literature review. Dental Press J Orthod 18: 150-157.

- Henrikson T, Nilner M, Kurol J (2000) Signs of temporomandibular disorders in girls receiving orthodontic treatment. A prospective and longitudinal comparison with untreated Class II malocclusions and normal occlusion subjects. Eur J Orthod 22: 271-281.

- Henrikson T, Ekberg EC, Nilner M (1997) Symptoms and signs of temporomandibular disorders in girls with normal occlusion and Class II malocclusion. Acta Odontol Scand 55: 229-235.

- Egermark I, Rönnerman A (1995) Temporomandibular disorders in the active phase of orthodontic treatment. J Oral Rehabil 22: 613-618.

- Ishigaki S, Basette R, Maruyama T (1993) Vibration of the temporomandibular joints with normal radiographic imagings: comparison between asymptomatic volunteers and symptomatic patients. Cranio 11: 88-94.

- Kuwahara T, Besette R, Maruyama T (1996) Characteristic chewing parameters for specific types of temporomandibular joint internal derangements. Cranio 14: 12-22.

- Mazmanoglu A (2016) Herkes ?çin Temel ?statistik Yöntemleri ve Uygulamalar?. McClave JT, Sincich T Statistic (eds.). Nobel Kitabevi, Istanbul, 1stedn. Prentice Hall, USA.

- Kerstein RB, Radke J (2016) Average chewing pattern improvements following Disclusion Time reduction. Cranio 35: 135-157.

LOGIN

LOGIN REGISTER

REGISTER.png)