Research Article

Implementation of a Clinical Practice Guideline to Assist Providers in Offering Uniform Birth Control Options to Postpartum Teens

Tammy Brunk* and Mary Ellen Wilkosz*

Department of Nursing, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, California, USA

*Corresponding authors: Tammy Brunk, Department of Nursing, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, California, USA, Tel: +1 7076642398; E-mail: brunk@sonoma.edu

Mary Ellen Wilkosz, Department of Nursing, Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, California, USA, Tel: +1 7076642297; E-mail: mary.wilkosz@sonoma.edu

Citation: Brunk T, Wilkosz ME (2017) Implementation of a Clinical Practice Guideline to Assist Providers in Offering Uniform Birth Control Options to Postpartum Teens. J Midwifery Womens Health Nurs Pract 2017: 10-19. doi:https://doi.org/10.29199/2637-9260/MWNP-101014

Received: 7 July 2017; Accepted: 27 September 2017; Published: 31 October 2017

Abstract

Teen pregnancy is a serious public health problem. The United States (US) has the highest rate of teenage pregnancy and teen births in the western industrialized world. More than one million teenage girls become pregnant each year at a cost of approximately 86 billion dollars which is an amount that is more than any other country spends on pregnancy related health care. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) have been shown to improve patient outcomes. This pilot study explored implementation of a post-partum contraceptive CPG in a rural Northern California hospital. Provider adherence to the implemented CPG was found to be successful with a 200% increase in post-partum contraceptive education for in-patient teen mothers.

Introduction

The United States (US) has the highest rate of teenage pregnancy, teen births, and sexually transmitted diseases in the western industrialized world and spends approximately 86 billion dollars on pregnancy related health care every year [1,2]. Two-thirds of teens that have babies will never graduate from high school [3]. While many teen moms do drop out of high school initially many eventually graduate or earn a GED. This data suggests that US teens practice high risk sexual behaviours. Although many teens are sexually active, many lack the knowledge of how to protect themselves from unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Strong evidence suggests that many teens find themselves in situations where they engage in unplanned sex and are not prepared to use contraception [4]. Although pregnancy rates have declined substantially over the past two decades for girls 15-19 years of age, it remains a serious public health issue. In 2013, a retrospective study titled, “The Impact of Antenatal Birth Control Education on Postpartum Initiation of Birth Control” [5] was performed in a rural community in Northern California. The county where the data was collected was ranked 48th highest among California’s 58 counties for teen pregnancy with a prediction for the teen birth rate to continue to rise for this county despite teen pregnancy rates declining at the state and national level [6]. The study explored whether the hospital or clinic had documented post-partum education for teen moms prior to discharge from the hospital as well as any pregnancy related clinic appointment. The data revealed that 39.3% of the time providers did not document any birth control counselling to teens in either the clinic or the hospital setting. It was determined that only 24.6% of teens received contraceptive education post-partum prior to discharge from the hospital. Retrospective review of the data found that obstetrical providers for the local hospital provided their own individualized postpartum contraceptive education [5]. However, there was a lack of consistent and coordinated postpartum birth control education provided to teens in the county. In addition, 45.9% of the time, teens did not return to the clinic for postpartum check-ups, suggesting a missed opportunity for education and initiation of postpartum contraception for teens [5]. Another significant finding of the study data was that 19.7% of the study population included second-time teen moms [5]. The literature supports that one in five teens will become a second-time mother within one to two years of their first birth. Rigsby et al., found that nearly 20% of teens have repeat pregnancies within two years of their first delivery [7]. The benefits of teen postpartum education to prevent repeat pregnancies has been demonstrated in multiple studies [8-11]. The outcome of this pilot study indicated there was local evidence of a gap in consistent provision of teen postpartum contraceptive education possibly contributing to the high rates of subsequent unplanned pregnancy in this group of teens. Utilization of the CPG would offer standardized postpartum contraception education with an opportunity for teens to initiate birth control prior to discharge from the hospital. Evidence indicates that there are positive benefits of postpartum education for adolescent mothers. The community hospital did not have a Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) in place for providers to use for postpartum contraceptive education specific to teen mothers. In response to the 2013 retrospective study findings, the author created a pilot study to evaluate how the local OB/GYN providers were using, and adhering to, a teen postpartum contraceptive CPG.

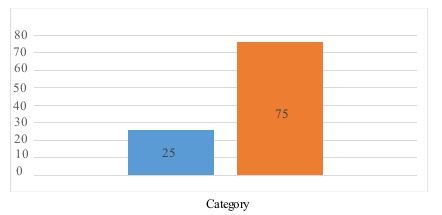

The CPG was developed from evidence found within the literature review and was implemented in a Northern California County. CPGs were developed to offer a systematic means to standardize patient treatment [12]. Evidence-based CPGs translate the best available research into recommendations to reduce unnecessary expenditures and provide for best practices [13]. The CPG developed for the study was based on two published guidelines from the CDC, Understanding and Using the US. Selected Practice Guidelines for Contraceptive Use [14] and Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use [15]. Other resources that were utilized for the development of the teen postpartum contraceptive CPG included the American Congress on Obstetrics and Gynaecology [16] and American Academy of Paediatrics [17]. Despite the evidence supporting the value of CPGs, [18] found that physicians lacked awareness of guidelines and had difficulty in applying guidelines to practice. Findings also indicate that more than 10% of physicians were not aware of the existence of CPGs in general. Lugtenberg et al., found that physicians self-reported barriers to adherence of CPGs were knowledge, attitude, and behaviour [12]. Successful implementation of CPGs for physicians occur most often within the trusting relationships of other providers, patient support and demand [19]. Another study found in order to achieve improved provider adherence, CPGs should have clear objectives and aims; strong evidence to support the guideline recommendations; and recommendations that are clear, specific, and are culturally sensitive to the target population [19]. The literature shows that provider adherence to CPGs is low, due to many perceived barriers during the implementation process. However, when CPGs are adhered to, the literature has shown improved patient outcomes (Figure 1). Burgers et al., considered the use of a CPG 70% to 100% of the time as having a high compliance rate [20]. These authors found that high compliance for decisions to follow recommendations of CPGs had similar attributes: required a new skill, not part of a complex decision tree, were compatible with existing norms and values in practice and supported with evidence. These attributes are found in the developed CPG for postpartum teen contraception, which positions the CPG for a high level of compliance. Protocols, checklists, and evidence-based guidelines have been shown to reduce patient harm because they allow for standardization and a reduction in unexplained variation of patient management [18]. The development of the US Medical Eligibility Criteria [15] and US Selected Practice Guideline are two evidenced-based tools developed to guide providers in standardizing contraceptive management [21,22]. ACOG endorses both tools and encourages use of these tools [18].

|

Figure 1: Percentage provider adherence to CPG. |

Methods

The project included a retrospective evaluation of the OB providers’ adherence to the teen postpartum contraceptive CPG. Provider education on the use of the teen postpartum contraceptive CPG was presented during a 60 minutes staff meeting with all six OB providers. Individual laminated copies of the CPG were provided to each OB provider (Appendix A).

A Power Point presentation with voice over was utilized to explain the CPG. Providers were assisted with downloading the cell phone application “CDC Contraception 2010” which is the electronic version of the US [15]. An interactive case study was presented which allowed for application of the CPG to a previous teen postpartum patient (Appendix B). Individual follow-up was provided within seven days of initial education to reinforce teaching and answering questions

Implementation of the teen postpartum contraceptive CPG was done in steps. A laminated paper copy of the teen postpartum contraception CPG was displayed on the census board located on the labour and delivery unit to ensure provider awareness. When a labouring teen presented, the OB provider was to offer her a bag containing sample postpartum contraceptive options and a teen postpartum contraceptive option education sheet (Appendix C). The OB provider would then offer verbal contraceptive education each day to the teen patient utilizing the sample contraceptive bag and the contraceptive education sheet. The OB provider would then document the contraceptive education discussion in the postpartum progress note, including which specific methods were under consideration by the teen. The decision of which method or declination of contraception would be documented prior to discharge.

The sample for the retrospective study included all female participants, ages 13 to 19 years of age that delivered babies from December 16, 2015 through March 30, 2016. Age, gravida, and para were recorded during the data collection process. Race was also included in the data tracking tool in order to evaluate cultural impact with regard to postpartum birth control initiation. Race was determined by patient self- reporting on the demographic sheet in each chart.

The quantitative data collected during the project was based on adherence to the teen postpartum contraception CPG. The data was collected over a 14 weeks period of time as teen patients presented for delivery. Several other indicators were collected for usage in the evaluation of the implementation of the CPG, but only the data collected regarding OB provider adherence to the CPG was used for analysis to determine if the project was successful. The other data indicators were collected for the purpose of evaluating the steps within the treatment process and used to make needed improvements to future usage of the CPG. The data tracking instrument (Appendix D) utilized in the project was developed because of the project’s unique data collection specificity. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the statistical significance of the categorical data in this project. A univariate analysis was used to analyse the data collected for the project question. The data provided a “yes” or “no” response, allowing for percentages to be found on adherence to the CPG. Aggregate data was collected for the purpose of future research.

Comparison of postpartum contraceptive education was made between the aggregate data and the CPG data to evaluate for statistical significance. Tabulation was performed on each category of aggregate demographic data and placed in a chart (Table 1). With the small sample size of five patients, limited statistical analysis was performed.

Table 1: Comparison Aggregate Demographic Data. Note: Comparison demographic collection included age, race, and gravida. Age 17 was the highest in the CPG group and second highest in the non-CPG comparison group. Caucasian was the most common race in both groups, then followed by Hispanic and then African American in the non-CPG group. All three races were represented in the small sample of the CPG group. A primigravida was the most common in both groups, but the small sample of five did include one second time pregnant teen as well as a teen that was transferred for severe preeclampsia and ultimately delivered a preterm infant. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

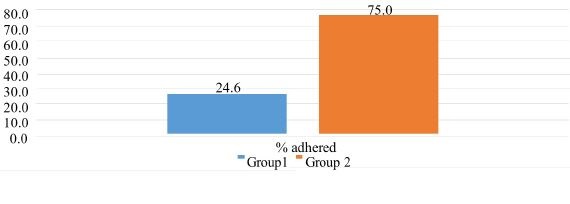

There were two opportunities to analyse demographic data. The first related to the CPG group only as no comparable data had been collected previously. The demographic data analysis was collected for categories of method chosen, method initiated, teen birth rate, and the individual OB provider’s use of the CPG. The second opportunity was to compare and analyse the two group’s demographic data of age, race, and gravida. The Chi Square test was used to evaluate any difference in the percentage of postpartum education received by comparison to adherence to the CPG. Minitab software was utilized in the process of performing the Pearson Chi Square test. Table 2 describes cross tabulation of comparison of provider delivery of contraceptive education. Statistical analysis performed using the chi square test was performed (Table 3) and a bar graph of patients that received postpartum contraceptive education was performed between the two groups (Figure 2). It was found that there was a statistical difference in the percent of postpartum contraceptive education received through adherence to the CPG in this project’s sample.

Table 2: Comparison Tabulation. Note: Describes cross tabulation of comparison of postpartum contraceptive education received by teen patients without the CPG and with the CPG. |

Table 3: Pearson Chi Square Statistical Analysis. Cell Contents: Count Expected count Contribution to Chi-square Pearson Chi-Square = 4.764, DF = 1, P-Value = 0.029; Note: 2 cells with expected counts less than 5. Note: The Chi Square test was used to evaluate any difference in the percentage of postpartum education received by comparison to adherence to the CPG. Minitab software was utilized in the process of performing the Pearson Chi Square test. It was found that there was a statistical difference in the percent of postpartum contraceptive education received through adherence to the CPG in this project’s sample. Based on the chi square analysis, the probability of the null hypothesis, that there is no change in the adherence rate being true, is very low of 2.9%. Usually this would lead one to automatically reject the null and accept the alternative hypothesis that the adherence rate had changed. However, the small sample size for CPG implementation leads us to this conclusion with a strong caution. Even though the chi square test shows a statistically significant change in the adherence rate based on the low p value, the validity of the conclusion is suspect as with such a small sample size for post CPG implementation, each individual observation can create a very large difference in the estimated percentage of adherence rate. This small sample size resulted in the expected count for two of the four cells in the contingency table to be less than 5. It would take a sample of approximately 17 births, at the estimated 70% adherence rate, to have enough data in each of the cells included in the table to remove the chance that each individual observation could change the overall adherence percent by a large amount. |

Figure 2: Percentage CPG of Postpartum Education by Group. Figure 2: Percentage CPG of Postpartum Education by Group. |

Results

For the purpose of this study, a compliance rate of 70% is considered a success of adherence to the CPG. The project question, “would obstetrical providers utilize a CPG at least 70% of the time” is a simple proportion test requiring a percentage answer. The project was deemed successful because 75% of the time providers utilized the CPG to educate the postpartum teen mothers on their contraceptive choices after offering provider education and implementation of the CPG. The six OB providers that are part of the study have different education levels, experience and skill sets. The demographics of the providers included two males and four females. Two of the providers were board certified OBGYNs, one provider was a family practitioner, and three Certified Nurse Midwifes (CNM). The OB providers share patients and one provider may not be the only provider caring for the teen patient using the CPG. Demographic data for the pregnant teens included age, race, and gravida (Table 1). Age 17 was the highest in the CPG group and second highest in the non-CPG comparison group. Caucasian was the most common race in both groups, then followed by Hispanic and then African American in the non-CPG group. All three races were represented in the small sample of the CPG group. A prima-gravida was the most common in both groups, but the small sample of five did include one second time pregnant teen as well as a teen that was transferred for severe preeclampsia and ultimately delivered a preterm infant. The first set of data evaluated was the non-comparable new project data. Table 4 demonstrates historical teen birth rates for the Northern California County including the teen birth rate for this project of 11.4%. The result validates that the sample size is representative of the expected and normal teen birth rate of county [5,6,23].

Table 4: Categorical Teen Birth Rates. Note: Table 1 demonstrates historical teen birth rates for the Northern California County including the teen birth rate for this project of 11.4%. The result validates that the sample size is representative of the expected and normal teen birth rate of the Northern California County [5,6,23]. |

Other collected demographic data included the birth control method chosen and the method initiated. Four opportunities to offer immediate postpartum contraception occurred during the project. The teen mothers chose Nexplanon 75% of the time and no offer of postpartum contraception occurred once (Table 5). None of the teen moms started a method prior to hospital discharge. Nexplanon was not offered in the hospital at the time of the study. However, it is currently available as a postpartum contraceptive option prior to discharge.

Table 5: Contraception Chosen. Note: Four opportunities to offer immediate postpartum contraception occurred during the project. The teen mothers chose Nexplanon 75% of the time and no offer of postpartum contraception occurred once. |

The definition of adherence is the complete following of the steps listed in the CPG. Non-adherence is defined as not consistent with following the steps of the CPG to its fullest capacity. It was found that the OB providers’ adherence to the teen postpartum contraceptive CPG was 75%, proving the project to be successful based on the project question (Table 5). Close examination of the CPG individual data would show that it did make positive strides in contraceptive education by the OB providers. As evidenced by the Data Tracking Instrument (Appendix E), the OB providers consistently utilized the protocol in the same manor. Three-fourths of the time, teens were given postpartum contraceptive education prior to their hospital discharge. Utilization of the CPG demonstrated improved postpartum contraceptive education consistency by a greater than 200% increase.

Based on the chi square analysis (Table 3), the probability of the null hypothesis, that there is no change in the adherence rate being true, is very low of 2.9%. This finding would usually lead one to automatically reject the null and accept the alternative hypothesis that the adherence rate had changed. However, since this was a pilot study with a small sample size for CPG implementation, caution must be taken in arriving at any conclusion. Even though the chi square test shows a statistically significant change in the adherence rate based on the low p value, the validity of the conclusion is suspect as with such a small sample size for post CPG implementation, each individual observation can create a very large difference in the estimated percentage of adherence rate. This small sample size resulted in the expected count for two of the four cells in the contingency table to be less than five. It would take a sample of approximately 17 births at the estimated 70% adherence rate to have enough data in each cells of the table to remove the chance that each individual observation could change the overall adherence percent by a large amount. Five out of six obstetrical providers had the opportunity to employ the CPG at least once. One per diem midwife did not have the opportunity to utilize the CPG due to the low number of qualifying patients. Three out of five were successful in adhering to the CPG (Table 6). Of those five providers, it was shown that two OB providers didn’t follow the CPG when working with a qualifying patient.

Table 6: CPG Usage. |

Discussion

Teens are a very vulnerable population. The literature demonstrates that teen pregnancy and repeat teen pregnancy is a significant and multifactorial problem [3,24]. Although this was a pilot study, a major benefit of this study was to identifying best practices to reduce the rates of unplanned, subsequent pregnancies in adolescents. Recidivism of pregnancy for teenagers is a problem that can impact their ability to become financially independent and educationally successful. The American health care system is impacted financially by the high cost of teen pregnancy and the adverse health outcomes [1]. While this pilot project was developed specifically for the OB team of the Northern California County, its implications on a large scale has potential to be far reaching. This project gives rise to opportunity for further research. Research focused directly on patient outcomes, financial benefits and nursing care of the teen postpartum patient would be further areas of interest. As well as examining how CPGs could provide more autonomy for providers and access to care for patients living in a rural area where there is a shortage of providers. Exploring whether or not CPGs are the best way to disseminate the latest evidence into practice would prove to be valuable. Studying whether incorporating the CPG’s into the electronic health record system, including offering prompts to the provider, and whether this would positively affect OB provider adherence, would also be a valuable idea for future research. In addition, investigating if CPGs have the same outcomes with patients in a vulnerable population vs. the general population would also provide valuable information to providers.

References

- Blingham D, Strauss N, Coeytaux F (2011) Maternal mortality in the United States: a human rights failure. Contraception 83: 189-193.

- Kearney MS, Lavine PB (2012) Why is the teen birth rate so high in the United States and why does it matter? J Econ Perspect 26: 141-166.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011) Vital signs: teen pregnancy - - - United States, 1991-2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60: 414-420.

- Brown S, Guthrie K (2010) Why don’t teenagers use contraception? A qualitative interview study. Eur J Contracept and Reprod Health Care 15: 197-204.

- Brunk T (2013) The impact of antenatal birth control education on post-partum initiation of birth control (Unpublished masters capstone). Colorado Mesa University, Colorado, USA.

- Barbara Aved Associates (2013) Identifying priority health needs. Lake County community health needs assessment. Pg no: 1-180.

- Rigsby DC, Macones GA, Driscoll DA (2005) Risk factors for rapid repeat pregnancy among adolescent mothers: a review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 11: 115-126.

- Kaplanoglu M, Kaplanoglu D, Usman MG (2014) Postpartum contraception in adolescents: data from a single tertiary clinic in southeast of Turkey. Glob J of Health Sci 7: 80-86.

- Lopez LM, Hiller JE, Grimes DA, Chen M (2012) Education for contraceptive use by women after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001863.pub3.

- Smith V (2014) Education for contraceptive use by women after childbirth. Practicing Midwife 17: 39-41.

- Trivedi D (2013) Cochrane review summary: education for contraceptive use by women after childbirth. Prim Health Care Res Dev 14: 109-112.

- Lugtenberg M, Burgers JS, Besters CF, Han D, Westert GP (2011) Perceived barriers to guideline adherence: a survey among general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract 12: 98.

- Hollon SD, Arean PA, Craske MG, Crawford KA, Kivlahan DR, et al. (2014) Development of clinical practice guidelines. Annu Rev in Clin Psychol 10: 213-241.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (2013) Committee Opinion No. 577: Understanding and Using the US Selected Practice Guidelines for Contraceptive Use, 2013. Obstetrics & Gynecology 122: 1132-1133.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists (2011) Committee Opinion No. 505: Understanding and Using the US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010. Obstetrics & Gynecology 118: 754-760.

- The American Congress on Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2013) Committee Opinion. American Academy of Pediatrics (2014) Contraception for Adolescents. Pediatrics 134: 1244-1256.

- The American Congress on Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2015) Clinical Guidelines and Standardization of Practice to Improve Outcomes Committee Opinion No. 629. Obstet Gynecol 125: 1027-1029.

- Hader J, White R, Lewis S, Foreman J, McDonald P, et al. (2007) Doctors’ views of clinical practice guidelines: a qualitative exploration using innovation theory. J Eval Clin Pract 13: 601-606.

- Burgers J, Grol R, Zaat J, Spies T, Akke K, et al. (2003) Characteristics of effective clinical guidelines for general practice. Br J Gen Pract 53: 15-19.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, United States.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) Vital signs: teen pregnancy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Georgia, United States.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013) Vital Signs: Repeat Births Among Teens - United States, 2007-2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62: 249-255.

- California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (2014) Maternal Data Center. California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, USA.

- Chen X, Wen S, Fleming N, Demissie K, Rhoads G, et al. (2007) Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a large population based retrospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 36: 368-373.

Appendix A: Teen Postpartum Contraceptive Clinical Practice Guideline

- All OB patients admitted to labour and delivery will be screened by her OB provider to evaluate if she meets the teen criteria of being age 13 to 19 years of age. If the patient is found to be a teen, the following steps will occur.

- The patient will be provided with a bag containing the teen postpartum contraceptive options education sheet and inactive sample methods of each contraceptive method by her provider either upon admission, in labour, or immediately postpartum. This sheet will include all approved contraceptive methods for immediate use postpartum: condom/spermicide, LARCs, and POPs. The verbal education provided will discuss all options included on the teen postpartum contraceptive education sheet with postpartum contraception options offered, including immediate IUD placement after delivery of the placenta. The discussion and chosen method or choices under consideration will be documented in the admission H&P. If the patient chooses an implant method, consent will be signed at that time.

- If patient chooses an IUD for immediate postpartum placement, the nurse will be notified and the device will be placed on the delivery table prior to delivery of the new born. Notation of the patient education, procedure, and consent will be included in the OB provider’s delivery note.

- On postpartum day 1, the OB provider will utilize contraceptive “sample” methods and reiterate education of each of the postpartum contraception methods approved from the patient’s bag. The OB provider will ask the patient to consider what birth control she is interested in receiving prior to discharge. The provider will answer any contraceptive questions that the teen may have at that time. The provider will encourage the patient to make a list of questions regarding postpartum contraception on the blank side of the sheet for further discussion prior to discharge. The teen patient will also be offered postpartum contraception initiation at that time.

- The OB provider will note in the postpartum progress note, day 1, that the teen postpartum contraceptive education sheet was discussed with specific methods under consideration by the teen patient. If the patient has declined contraception, that will also be noted.

- Steps #5 and #6 will be repeated until discharge.

- On the discharge day, the OB provider will perform step #5 and provide initiation of contraceptive method. The OB provider will note this final decision/implementation of the contraceptive method in the discharge note in the EMR system, including declination of contraception by the teen if applicable.

Appendix B: Interactive Case Study Case Study.

Your patient is a 19-year-old female, who delivered her second infant two days ago and is being discharged today. She is breastfeeding. You are providing her postpartum contraceptive education and discussing what method would be a good option for her to start. Together, you go over the teen postpartum contraceptive education sheet. The patient notices that the “pill” is listed as a choice. She had used combined oral contraceptive pills before she was pregnant and would like to start using them again.

Appendix C: Teen Patient Postpartum Contraceptive Options Education Sheet.

|

Appendix D: Data Tracking Instrument

|

|

Appendix E: OB provider.

|

LOGIN

LOGIN REGISTER

REGISTER.png)