Review article

Topical Issues in Translational Pharmacology and Pharmaceuticovigilance: Can Pharmacological Research on Birth Control and Contraception Meet the Requirements of Bioethical Standards?

Kurt Kraetschmer*

Austrian-American Medical Research Institute, Agnesgasse 11, 1090 Vienna, Austria

*Corresponding author: Kurt Kraetschmer, Austrian-American Medical Research Institute, Agnesgasse 11, 1090 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: kurt.kraetschmer@aon.at

Citation: Kraetschmer K (2019) Topical Issues in Translational Pharmacology and Pharmaceuticovigilance: Can Pharmacological Research on Birth Control and Contraception Meet the Requirements of Bioethical Standards? J Pharm Sci Exp Pharmacol 2019: 06-11.

Received Date: 30th August 2019; Accepted Date: 01st October 2019; Published Date: 12th October 2019

Abstract

Aim: On the background of media reports about serious harm to the health of thousands of women engaged in birth control and contraception, the research article aims at emphasizing the importance of pharmaceuticovigilance for information on the safe use of contraceptive pills and devices.

Method:

The method consists in an in-depth analysis of those sources of information that are most widely used by women and their healthcare providers, ie, patient information leaflets and packaging labels of manufacturers; statements by governmental health agencies; publications by the European Medicines Agency (EMA); and infromation by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In addition, findings contained in high-ranked scholarly journals, especially those in pharmacovigilance, are critically surveyed.

Results:

Presently, women are not provided with information suitable for safe contraceptive pursuits. Consumers are not adequately informed about contraceptive products as pharmaceutical companies frequently fail to comply with the principle of informed consent. Clinicians, under the pressure of economic maxims such as cost efficiency, apparently fail to convey salient information to their patients.

Conclusion:

As it is difficult for women to obtain accurate, complete, comprehensible and reliable information on the safety of methods of contraception, especially on vital pharmacological parameters, they are advised to intensify autodidactic strategies by using not only print media but also social media via internet.

Intensification of pharmacological education should be pursued not only by individual healthcare providers but also by editors who frequently publish studies obscured by conflicts of interest. To remedy the lack of vital information for the consumer and to avoid detrimental consequences for women's health research in pharmaceuticovigilance – whose foundation is laid within this article – should be intensified.

Keywords: Contraception; Emergency and oral hormonal contraception; Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC); Periodic abstinence/fertility awareness; Pharmaceuticovigilance; Pharmacology; Sterilization.

Introduction

Recently, one of the world's leading pharmaceutical companies became the target of press reports commenting on complaints lodged by women who had experienced severe adverse events associated with the company's product for permanent contraception. According to these reports, not only medical problems were at stake but also forensic issues owing to thousands of lawsuits filed against the company. ‘‘The implant has had a troubled history. It has been the subject of an estimated 16,000 lawsuits or claims filed by women who reported severe injuries, including perforation of the uterus and the fallopian tubes. Several deaths, including of a few infants, have also been attributed to the device or to complications from it’’ [1].

From Australia similar reports reached the international readership: ‘‘The device, known as Essure, is a soft, flexible insert placed into each of the patient’s fallopian tubes. Over three months a barrier forms around the inserts, which is intended to block the fallopian tubes and permanently prevent pregnancy. But there have been reports women experienced changes in menstrual bleeding, unintended pregnancy, chronic pain, perforation and migration of the device, allergic reactions and immune-type reactions after being implanted with the device, which is manufactured by the pharmaceutical company Bayer’’ [2].

The medical and legal problems affecting the company's business in a negative fashion originated from a small nickel-titanium coil designed for permanent contraception by way of sterilization. In its instructions for use the company explains the components of the device and defines it as an insert. As such, the consumer envisages it as a foreign object that is inserted into a woman's body similar to a diaphragm or a patch. ‘‘Each insert consists of a Nitinol (nickel-titanium alloy) outer coil, a 316L stainless steel inner coil wrapped in polyethylene terephtalate (PET) fibers, platinum marker bands (2) and a silver-tin solder’’. The Instructions for Use offer information also on the characteristics of the device concerning length and diameter: ‘‘The insert is 4 cm in length and 0.8 mm in diameter in its wound-down configuration’’. As soon as the outer coil is released it expands up to 2.0 mm in diameter ‘‘conforming itself to the varied diameters and shapes of the fallopian tube [3].

As part of their marketing strategy the company emphasized the unique feature of the device by referring to the FDA. ‘‘Essure is the only FDA-approved non-incisional form of permanent birth control’’ [4]. Concerning the mechanism of action the company specifies that the ‘‘Essure system’’ is intended for permanent contraception by means of a ‘‘physical occlusion of the fallopian tubes’’ [3]. Through a transvaginal manoeuvre the Essure system is placed into the lumen of the proximal portion of the fallopian tube where it anchors upon release: ‘‘The insert is a dynamic and flexible spring-like device. The outer coil expands upon deployment, conforms to and pushes against the fallopian tube wall, acutely anchoring the insert in the lumen of the fallopian tube’’ [3]. Dynamic anchoring in the fallopian tube, however, does not suffice to effect contraception; rather it is the occlusion of the fallopian tube through a tissue in-growth that results in sterilization. ‘‘Subsequently, the insert elicits a benign tissue in-growth that permanently occludes the lumen of the fallopian tube, resulting in permanent contraception’’ [3].

Although the company felt compelled to withdraw its product from the Australian market in 2017 – under the pressure of the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (ATGA)[5] -- and from the US market by the end of 2018, it continued to insist on both efficacy and safety of the device. Thus, in its News Release of 2018 announcing the withdrawal from the US market, the company stressed the research undertaken, which had involved more than 200.000 women. ‘‘The benefit-risk profile of Essure has not changed, and we continue to stand behind the product’s safety and efficacy, which are demonstrated by an extensive body of research, undertaken by Bayer and independent medical researchers, involving more than 200,000 women over the past two decades’’[4].

As its strongest argument for the safety of the device the company can refer to a statement made by the FDA drawing attention to a comparison of benefits and risks. ‘‘The FDA has maintained for several years that the benefits of Essure outweigh its risks’’[4].

Despite insistence on the safety of the device, the company felt compelled in 2018 to draw attention to severe adverse events by providing important safety information including an explicit warning: ‘‘Some patients implanted with the Essure System for Permanent Birth Control have experienced and/or reported adverse events, including perforation of the uterus and/or fallopian tubes, identification of inserts in the abdominal or pelvic cavity, persistent pain, and suspected allergic or hypersensitivity reactions. If the device needs to be removed to address such an adverse event, a surgical procedure will be required. This information should be shared with patients considering sterilization with the Essure System of Permanent Birth Control during discussion of the benefits and risks of the device’’[4].

As early as 2002, the company issued general warnings regarding perforation, embedment, and expulsion: ‘‘Unsatisfactory device location including perforation, uterine embedment and expulsion may result in pain’’. Warnings about the risk of pregnancy draw attention also to some serious conditions: ‘‘While most pregnancies with Essure in situ have been reported as healthy deliveries at term, pregnancy loss, pre-term labor, pre-term rupture of membranes, pre-term delivery, stillbirth, and neonatal complications have also been reported’’. The hysteroscopist is advised to reduce the risk of hypervolemia and pay attention to the possibility of tubal perforation: “Terminate the procedure if distention fluid deficit exceeds 1500cc, to reduce the risk of hypervolemia’’. As excess fluid deficit can be a sign of uterine or tubal perforation, the procedure should be discontinued and the patient evaluated “for possible perforation’’[3].

The “Patient Counseling Information’’ contained in the Instructions for Use warns about allergies to nickel or other component parts of the insert subsequent to placement. “Typical allergic symptoms reported for this device include hives, urticaria, rash, angioedema, facial edema and pruritis /sic!/’’. The manufacturer requests, therefore, that all patients be counseled on the materials contained in the insert and on the “potential for allergy/hypersensitivity prior to the Essure procedure’’. Patients are advised to familiarize themselves with the “Patient Information Booklet (PIB)’’[3]. The doctor should review with the patient the ‘‘Patient-Doctor Discussion Checklist,’’ and all of the patients' questions should be answered.

According to the instruction for use of 2002, adverse events resulting from the placement procedure include cramping, pain, nausea/vomiting, dizziness/light headedness, bleeding/spotting, vaso-vagal response, hypervolemia, and band detachment. Among the risks with follow-up procedures allergic reaction is mentioned owing to the use of contrast media for the modified Hysterosalpingography (HSG), and the lethal consequences of an anaphylactic response are described: “Allergic reaction can result in hives or difficulty breathing. In some individuals, an anaphylactic response may occur which may lead to death’’[3].

In a section entitled Directions for Use, attention is drawn to ovulation day calculations and to pretreatment. ‘‘Women with menstrual cycles shorter than 28 days should undergo careful ovulation day calculations. Insert placement should not be performed during menstruation’’. Visualization for the hysteroscopist can be improved through pretreatment for suppression of endometrial proliferation. ‘‘Pretreatment of the patient with medications that suppress endometrial proliferation may enhance visualization and scheduling flexibility’’[3].

As can be seen from the Directions for Use copyrighted in 2002, there are numerous warnings and precautions about risks and adverse events. The ‘‘News Release’’ of 2018 contains again warnings and draws attention to immunosuppressants as well as allergies to metal, polyester fibers, nickel, titanium, platinum, silver-tin, stainless steel and other components of the Essure system. Moreover, it explains adverse events that can occur during and subsequent to the procedure of inserting the device into the fallopian tube. During the procedure, it is possible that the device is placed incorrectly, that part of it breaks off, and that perforation through the hysteroscope occurs with ensuing need for surgery. ‘‘During the Procedure: In the premarketing study, some women experienced mild to moderate pain (9.3%). Your doctor may be unable to place one or both Essure inserts correctly. In rare cases, part of an Essure insert may break off during placement. If breakage occurs, your doctor will remove the piece, if appropriate’’[4]. The complications due to a perforation are appropriately described. ‘‘There is a risk of perforation of the uterus or fallopian tube by the hysteroscope, Essure system or other instruments used during the procedure. In the original premarket studies, perforation due to the Essure insert occurred in 1.8% of women. A perforation may lead to bleeding or injury to bowel or bladder, which may require surgery. Your doctor may recommend a local anesthesia. Ask your doctor about the risks associated with this type of anesthesia’’[4].

Subsequent to the procedure pain, cramping, and vaginal bleeding may occur. ‘‘Immediately Following the Procedure: In the premarketing study, some women experienced mild to moderate pain (12.9%) and/or cramping (29.6%), vaginal bleeding (6.8%), and pelvic or back discomfort for a few days. Some women experienced headaches, nausea and/or vomiting (10.8%), or dizziness and/or fainting. . . In rare instances, an Essure insert may be expelled from the body’’[4].

Adverse events can occur also several weeks after the insertion procedure, during the so-called Essure confirmation test. ‘‘As one of the Essure Confirmation Tests (a modified HSG) requires an x-ray, you may be exposed to very low levels of radiation, as with most x-rays, if this test is used. Some women may experience nausea and/or vomiting, dizziness and/or fainting, cramping, pain or discomfort. In rare instances, women may experience spotting and/or infection’’ [4].

In addition to adverse events during the insertion, after insertion, and during the confirmation test, there are risks that must be considered long-term. The most perilous of these risks is ectopic pregnancy, and, as the manufacturer warns, this can be life-threatening. ‘‘Long-term Risks: Pain (acute or persistent) of varying intensity and length of time may occur and continue following Essure placement. . . . Patients with known hypersensitivity to any of the components of the Essure system may experience an allergic reaction to the insert’’ [4]. Subsequent to placement, the manufacturer specifies, some women may develop an allergy to nickel or other component parts of the insert. The symptoms reported by users of Essure may be associated with allergic reactions and include hives, rash, swelling and itching. Concerning the risk of ectopic pregnancies the manufacturer correctly underscores the seriousness of the condition. ‘‘This can be life-threatening. If insert removal is indicated, surgery will be necessary’’[4]. Concerning special populations, the manufacturer specifies that neither safety nor efficacy have been established for women under 21 or over 45 years of age. ‘‘The safety and effectiveness of Essure has not been established in women under 21 or over 45 years old’’[4].

As a particular safety measure, the manufacturer restricted the insertion procedure of the device to physicians who are competent hysteroscopists: ‘‘Caution: Federal law restricts this device to sale by or on the order of a physician. Device to be used only by physicians who are knowledgeable hysteroscopists; have read and understood the Instructions for Use and Physician Training Manual; and have successfully completed the Essure training program, including preceptoring in placement until competency is established, typically 5 cases’’ [4].

As can be seen from the above citations, the manufacturer (Essure) endeavored to provide comprehensive information on the device and mentions also the life-threatening risks of an anaphylactic reaction and of an ectopic pregnancy. At the same time, however, the consumer notices that the information is not always as comprehensible as required by the bioethical principle of informed consent, which stipulates that the patient be enabled to make ‘‘an intelligent choice’’ [6]. Thus in explaining the mechanism of action the company uses a nomenclature that might be confusing not only to unexperienced consumers but even to educated healthcare providers because it is unclear what kind of biochemical process can ‘‘elicit’’ a benign-tissue in-growth, as specified by the manufacturer: ‘‘Subsequently, the insert elicits a benign tissue in-growth that permanently occludes the lumen of the fallopian tube, resulting in permanent contraception’’ [3]. In a different context tubal occlusion and tissue in-growth are explained with reference to PET fibers, ie, ‘‘polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fibers’’. Allegedly, these fibers cause tissue in-growth which facilitates not only retention of the device but also tubal occlusion. ‘‘Tubal occlusion is attributed to the space filling design of the device and the benign occlusive tissue response. PET fiber causes tissue in-growth into and around the insert, facilitating insert retention, resulting in tubal occlusion and contraception’’ [3].

From a physiological viewpoint it is difficult to understand by what kind of chemical reaction the device can ‘‘elicit’’ a benign tissue in-growth. It is not surprising therefore that alternative explanations have been provided which assume an inflammation and ensuing fibrotic growth. ‘‘The small, flexible inserts are made from polyester fibers, nickel-titanium, stainless steel and solder. The insert contains inner polyethylene terephthalate fibers to induce inflammation, causing a benign fibrotic ingrowth’’ [7].

Press reports too avoided the expression ‘‘in-growth’’ and spoke of ‘‘scar’’ tissue, ie, tissue which results from a wound inflicted to healthy tissue. ‘‘Essure consists of two nickel-titanium coils inserted into the fallopian tubes, where they spur the growth of scar tissue that blocks sperm from fertilizing a woman’s eggs’’[1]. By medical definition, a scar is ‘‘a permanent mark resulting from a wound or disease process in tissue’’[8]. If the insert does in fact cause a wound ethical standards require that the consumer be informed accordingly.

Concerning wounds and ‘‘ingrowth’’ it should be borne in mind that the resemblance between wound healing and tumor growth have been cogently outlined as early as 1986 in a publication focusing on the similarities between wound healing and tumor growth. In describing tumors as wounds that do not heal, the author concludes: ‘‘They have developed the capacity to preempt and subvert the wound-healing response of the host as a means to acquire the stroma they need to grow and expand. They mimic wounds by depositing an extravascular fibrin-fibronectin gel. Such gels, in tumors as at sites of local injury, signal the host to marshal the wound-healing response. This response is stereotyped and similar in both tumors and wounds. In tumors, however, the fibrin-fibronectin matrix signal that evokes the wound-healing response is not selflimited; it continues to operate and new gel is continuously deposited. Thus, tumors appear to the host in the guise of wounds or, more correctly, of an unending series of wounds that continually initiate healing but never heal completely [9].

As can be seen from the foregoing discussion of the Essure implant for permanent contraception, one of the reasons that caused the troubled history of the device is information unsuited to enable the patient to make an intelligent choice. The problem of inadequate information is not a specificity of the insert for permanent contraception discussed above; it is a crux also in other descriptions of products for birth control and contraception. It seems appropriate therefore to investigate as to whether or not pharmaceutical companies manufacturing pills and devices for birth control and contraception can stand up to the ethical standards of the principle of informed consent which requires comprehensive and comprehensible information for the patient [6].

The subsequent sections are devoted to such an investigation and aim at bringing to light deficits and shortcomings in information provided by pharmaceutical companies. Given that Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC), oral hormonal contraceptives, and pills for Emergency Contraception are the most widely used forms of contraception, the pharmaceutical companies producing these pills and devices are the focal points.

LARC – the most effective form of contraception

LARC comprise implants and intrauterine devices and are considered the most effective form of contraception owing to estimates of 0.05% for implants, 0.2% for levonorgestrel containing intrauterine devices, such as Mirena, [10] and 0.6 (perfect use/0.8 typical use) for copper containing such as ParaGard.

The Etonogestrel implants (Nexplanon and Implanon):

Information on the etonogestrel-containing implants furnished by the manufacturer is available as a 52-page ‘‘Patient Information Leaflet’’ containing various headings, namely a Highlights of Prescribing Information, a Full Prescribing Information for Nexplanon [I] (comprising 14 pages), a FDA-Approved Patient Labeling for Nexplanon[II](comprising 5 pages), a Highlights of Prescribing Information and a Full Prescribing Information for the etonogestrel implant Implanon, and a FDA-Approved ‘‘Patient Labeling IMPLANON® (etonogestrel implant), Subdermal Use’’ [III], comprising 11 pages [11].

The Full Prescribing Information specifies that Nexplanon is a progestin-only, flexible and soft radiopaque implant. Destined for subdermal use, it is preloaded in a disposable sterile applicator. The length of the white/off-white, non-biodegradable implant is 4 cm, and its diameter is 2 mm. Its ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) copolymer core contains 68 mg etonogestrel (a synthetic progestin), barium sulfate (radiopaque ingredient), but may contain also magnesium stearate, surrounded by an EVA copolymer skin. ‘‘Once inserted subdermally, the release rate is 60-70 mcg/day in week 5-6’’. Thereafter it decreases to about 35-45 mcg per day by the end of the first year; by the end of the second year it decreases to about 30-40 mcg per day, and by the end of the third year to approximately 25-30 mcg per day. As Nexplanon is a progestin-only implant it does not contain estrogen; it neither contains latex [11].

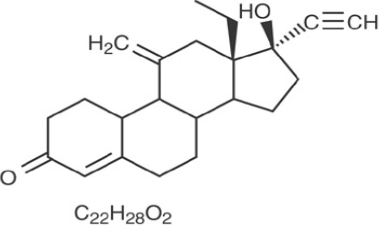

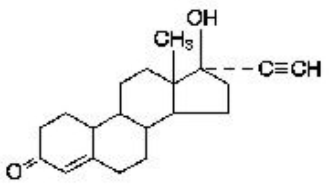

Etonogestrel [13-Ethyl-17-hydroxy-11-methylene-18,19-dinor-17α-pregn-4-en-20-yn-3-one], is structurally derived from 19-nortestosterone, which is the synthetic biologically active metabolite of the synthetic progestin desogestrel. It has a molecular weight of 324.46 and the following structural formula [11] (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: Etonogestrel. |

Concerning clinical pharmacology, the mechanism of action consists in suppressing ovulation, in increasing the viscosity of the cervical mucus, and in altering the endometrium.

Regarding pharmacodynamics, it has been admitted that exposure-response relationships of the etonogestrel implants are unknown. With respect to pharmacokinetics it is assumed that absorption takes place subsequent to subdermal insertion of the etonogestrel implant. Etonogestrel is released into the circulation and is approximately 100% bioavailable. The serum concentration for Nexplanon was established on the basis of a three-year clinical trial. The mean (plus-minus SD) maximum serum etonogestrel concentrations were 1200 (plus-minus 604) pg/mL; they were reached within the first two weeks following implantation (n=50). The mean (plus-minus SD) serum etonogestrel concentration decreased gradually over time, reaching 202 (plus-minus 55) pg/mL by the end of the first year (n=41), reached 164 (plus-minus 58) pg/mL by the end of the second year (n=37), and reached 138 (plus-minus 43) pg/mL by the end of the third year. (n=32). In the case of the non-radiopaque implant Implanon, a precursor of Nexplanon, the mean (plus-minus SD) maximum concentration of etonogestrel were 1145 (plus-minus 577) pg/ml attained within two weeks after implantation [11].

Concerning distribution the manufacturer states that the apparent volume of distribution averages about 201 L. Approximately 66% of etonogestrel is bound to albumin in blood and 32% is bound to sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG). As regards metabolism, in vitro data indicate that etonogestrel is metabolized in microsomes of the liver by the cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme. Regarding the biological activity of etonogestrel metabolites no data are available. Concerning excretion, according to the manufacturer, the elimination half-life of etonogestrel is approximately 25 hours. Excretion of etonogestrel and its metabolites -- as free steroid or as conjugates -- is primarily in urine and to a minor extent in feces [11].

Besides details of clinical pharmacology the ‘‘Full Prescribing Information’’ furnished by the manufacturer contains important information also on contraindications, warnings and precautions, adverse reactions, drug interactions and use in specific populations [11]. As regards contraindications several conditions are enumerated, namely known or suspected pregnancy, current or past history of thrombosis or thromboembolic disorders, liver tumors, benign or malignant (or active liver disease), undiagnosed abnormal genital bleeding, known or suspected breast cancer (personal history of breast cancer, or other progestin-sensitive cancer, presently or in the past), allergic reaction to any of the components of Nexplanon [11].

Complications pertaining to insertion and removal procedures include pain, paresthesias, bleeding, hematoma, scarring or infection. The manufacturer warns about incorrectly inserted implants and describes potential complications of removal. ‘‘Removal of deeply inserted implants should be conducted with caution in order to prevent injury to deeper neural or vascular structures in the arm’’ and should therefore be performed by a physician knowledgeable in the anatomy of the upper extremity. If the implant is not removed the effects of etonogestrel will continue and result in ‘‘compromised fertility, ectopic pregnancy, or persistence or occurrence of a drug-related adverse event’’[11].

Regarding Changes in Menstrual Bleeding Patterns, the manufacturer specifies that subsequent to initiating contraception with Nexplanon, patients will most likely experience a change of their normal menstrual bleeding pattern. ‘‘These may include changes in bleeding frequency (absent, less, more frequent or continuous), intensity (reduced or increased) or duration’’ [11]. Pertaining to ectopic pregnancy, which is possible with all progestin-only contraceptive products, caution should be exercised in case of pregnancy or lower abdominal pain. ‘‘Although ectopic pregnancies are uncommon among women using NEXPLANON, a pregnancy that occurs in a woman using NEXPLANON may be more likely to be ectopic than a pregnancy occurring in a woman using no contraception’’ [11].

As regards thrombotic and other vascular events, the manufacturer calls to mind that combination hormonal contraceptives containing both progestin and estrogen increase the risk of arterial events such as stroke and myocardial infarction as well as deep venous thrombotic events, such as venous thromboembolism, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and retinal vein thrombosis. As Nexplanon is a progestin-only contraceptive, it is not known whether these increased risks are relevant for etonogestrel alone. ‘‘It is recommended, however, that women with risk factors known to increase the risk of venous and arterial thromboembolism be carefully assessed’’ [11].

Regarding ovarian cysts, the manufacturer explains that atresia of the follicle is sometimes delayed in case of follicular development ‘‘and the follicle may continue to grow beyond the size it would attain in a normal cycle’[11]. With respect to carcinomas of the breast and reproductive organs, the manufacturer recommends that women with current or past breast cancer ‘‘should not use hormonal contraception because breast cancer may be hormonally sensitive’’. Attention is drawn also to studies suggesting an association between the use of combination hormonal contraceptives and an increased risk of intraepithelial neoplasias or cervical cancer. ‘‘Women with a family history of breast cancer or who develop breast nodules should be carefully monitored’’ [11].

Concerning liver disease the manufacturer recommends removal of Nexplanon if there is a development of jaundice and draws attention to the association between hepatic adenomas and combination hormonal contraceptives (estimate of the attributable risk is 3.3 cases per 100.000 users). Whether a similar risk can be assumed for progestin-only contraceptives, such as Nexplanon, is unknown [11]. Weight gain occurred during use of the non-radiopaque etonogestrel implant Implanon and was 2.8 pounds after one year and 3.7 pounds after two years. Concerning elevated blood pressure, the manufacturer recommends that women with a history of hypertension-related diseases or renal diseases abstain from using hormonal contraception. As regards gallbladder disease, the manufacturer mentions studies suggesting a slight increase in the relative risk of developing gallbladder disease among users of combination hormonal contraceptives. Whether this holds true also for progestin-only contraception is unknown.

Pertaining to carbohydrate and lipid metabolic effects the manufacturer mentions the possibility of a mild insulin resistance and slight changes in glucose concentrations due to Nexplanon. ‘‘Women who are being treated for hyperlipidemia should be followed closely if they elect to use NEXPLANON. Some progestins may elevate LDL levels and may render the control of hyperlipidemia more difficult’’ [11]. With regard to depressed mood the manufacturer recommends careful observation of women with a history of such a condition and advises removal of Nexplanon ‘‘in patients who become significantly depressed’’ [11].

Regarding return to ovulation the manufacturer specifies that in clinical trials with Implanon, pregnancies occurred as early as seven to fourteen days after removal. ‘‘Therefore, a woman should re-start contraception immediately after removal of the implant if continued contraceptive protection is desired’’ [11]. Fluid retention, according to the manufacturer, can be caused by hormonal contraceptives so that caution should be exercised in prescribing them for patients ‘‘with conditions which might be aggravated by fluid retention’’ [11]. Whether Nexplanon causes fluid retention is not known. Concerning contact lenses the manufacturer advises that in case of visual changes or changes in lens tolerance assessment by an ophthalmologist be sought.

In response to reports of broken or bent implants in the patient’s arm, the manufacturer specifies that the release rate of etonogestrel may be slightly increased. Women implanted with Nexplanon should be monitored and have the possibility of ‘‘a yearly visit with her healthcare provider for a blood pressure check and for other indicated health care’’ [11]. Concerning drug-laboratory test interactions the manufacturer draws attention to sex hormone-binding globulin and thyroxine. ‘‘Sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations may be decreased for the first six months after NEXPLANON insertion followed by gradual recovery. Thyroxine concentrations may initially be slightly decreased followed by gradual recovery to baseline’’ [11].

In discussing adverse reactions associated with the use of hormonal contraception, the manufacturer draws attention again to changes in menstrual bleeding patters, ectopic pregnancies, thrombotic and other vascular events, and liver disease. In presenting statistical data pertaining to adverse reactions the manufacturer focuses on the non-radiopaque implant Implanon and not on Nexplanon. Those adverse reactions which result in a rate of discontinuation of Implanon greater or equal to 1% include: bleeding irregularities, emotional lability, weight increase, headache, acne, and depression. Adverse reactions reported by 5% (or more) in trials with Implanon include headache (24.9%), vaginitis (14.5%), weight increase(13.7%), acne (13.5%), breast pain (12.8%), pharyngitis (10.5%), leukorrhea (9.6%), influenza-like symptoms(7.6%), dizziness (7.2%), dysmenorrhea (7.2%), back pain (6.8%), emotional lability (6.5%), nausea (6.4%), pain (5.6%), nervousness (5.6%), depression (5.5%), hypersensitivity (5.4%), and insertion site pain (5.2%) [11].

Concerning implant site, the manufacturer mentions a clinical trial which examined this location subsequent to insertion of Nexplanon and found that 8.6% of women reported reactions. ‘‘Erythema was the most frequent implant site complication, reported during and/or shortly after insertion, occurring in 3.3% of subjects. Additionally, hematoma (3.0%), bruising (2.0%), pain (1.0%), and swelling (0.7%) were reported’’[11]. Additional adverse reactions to Implanon were brought to light by postmarketing experience, identified during post-approval use and reported voluntarily from a population of uncertain size. The adverse reactions reported include: gastrointestinal disorders (constipation, diarrhea, flatulence, vomiting); general disorders and conditions of administration site (edema, fatigue, implant site reaction, pyrexia); immune system disorders (anaphylactic reactions); infections and infestations (rhinitis, urinary tract infection); investigations (clinically relevant rise in blood pressure, weight decreased); metabolism and nutrition disorders (increase in appetite); musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (arthralgia, musculoskeletal pain, myalgia); [11] nervous system disorders (convulsions, migraine, somnolence); pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions (ectopic pregnancy); psychiatric disorders (anxiety, insomnia, decrease of libido); renal and urinary disorders (dysuria); reproductive system and breast disorders (breast discharge, breast enlargement, ovarian cyst, pruritus genitalis, vulvovaginal discomfort); skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (angioedema, aggravation of angioedema and/or aggravation of hereditary angioedema, alopecia, chloasma, hypertrichosis, rash, pruritus, urticaria, seborrhea); vascular disorders (hot flush). Among the complications related to the insertion or removal procedures of Implanon were ‘‘bruising, slight local irritation, pain or itching, fibrosis at the implant site, paresthesia or paresthesia-like events, scarring and abscess’’[11].

With respect to changes in contraceptive efficacy due to coadministration of other products the manufacturer draws attention to the induction of enzymes, including CYP3A4, that metabolize progestins. They may cause a reduction in the plasma concentrations of progestins and may therefore decrease the effectiveness of Nexplanon. ‘‘In women on long-term treatment with hepatic enzyme inducing drugs, it is recommended to remove the implant and to advise a contraceptive method that is unaffected by the interacting drug’’[11]. Among the drugs or herbal products inducing enzymes, including CYP3A4, the following are listed: barbiturates, bosentan, carbamazepine, felbamate, griseofulvin, oxcarbazepine, phenytoin, rifampin, St. John’s wort, and topiramate. In this context, the manufacturer draws attention also to HIV antiretrovirals, since significant changes (decrease or increase) in the progestin plasma levels have been noted ‘‘in some cases of co-administration with HIV protease inhibitors or with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors’’[11].

In discussing the use of Nexplanon in specific populations the manufacturer addresses problems of pregnant women, nursing mothers, pediatric use, geriatric use, hepatic impairment, renal impairment, and overweight women. Concerning pregnancy, the manufacturer states that the implant is not for use during pregnancy and refers to teratology studies which did not produce any evidence of fetal harm due to etonogestrel exposure. ‘‘Studies have revealed no increased risk of birth defects in women who have used combination oral contraceptives before pregnancy or during early pregnancy. There is no evidence that the risk associated with etonogestrel is different from that of combination oral contraceptives’’ [11].

Concerning nursing mothers, the manufacturer admits that only limited clinical data are available: ‘‘NEXPLANON may be used during breastfeeding after the fourth postpartum week. Use of NEXPLANON before the fourth postpartum week has not been studied’’ [11]. Available data indicate that etonogestrel is excreted in breast milk so that 100 ng might be ingested by the child during the first month, and the daily infant etonogestrel dose one month after insertion of the device is approximately 2.2% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose. ‘‘Small amounts of etonogestrel are excreted in breast milk. During the first months after insertion of NEXPLANON, when maternal blood levels of etonogestrel are highest, about 100 ng of etonogestrel may be ingested by the child per day based on an average daily milk ingestion of 658 mL. Based on daily milk ingestion of 150 mL/kg, the mean daily infant etonogestrel dose one month after insertion of the non-radiopaque etonogestrel implant (IMPLANON) is about 2.2% of the weight-adjusted maternal daily dose, or about 0.2% of the estimated absolute maternal daily dose’’ [11]. In discussing issues pertaining to nursing mothers, attention is drawn also to non-hormonal contraceptives which might be an alternative option: ‘‘Healthcare providers should discuss both hormonal and non-hormonal contraceptive options, as steroids may not be the initial choice for these patients’’[11].

Concerning pediatric use the manufacturer claims that safety as well as efficacy of Nexplanon have been established for women of reproductive age. ‘‘Safety and efficacy of NEXPLANON are expected to be the same for postpubertal adolescents’’ [11]. Unfortunately, no data are provided to substantiate this precarious claim, and the assumption concerning postpubertal adolescents is no more than speculative. For users less than 18 years no studies have been undertaken. ‘‘However, no clinical studies have been conducted in women less than 18 years of age. Use of this product before menarche is not indicated’’ [11].

Concerning specific populations with hepatic impairment the manufacturer admits that no studies are available ‘‘to evaluate the effect of hepatic disease on the disposition of NEXPLANON’’ [11]. The same holds true for women suffering from renal impairment: ‘‘No studies were conducted to evaluate the effect of renal disease on the disposition of NEXPLANON’’ [11]. As regards overweight women the manufacturer calls to mind the inverse relationship between etonogestrel serum concentrations and body weight. Consequently, the possibility exists ‘‘that NEXPLANON may be less effective in overweight women, especially in the presence of other factors that decrease serum etonogestrel concentrations such as concomitant use of hepatic enzyme inducers’’ [11].

Besides the Full Prescribing Information discussed above, the manufacturer offers also a FDA-Approved Patient Labeling. In this piece of information users are advised that NEXPLANON implant must be removed after 3 years. As regards the mechanism of action, thickening of the cervical mucus to prevent contact between ovum and sperm is underlined, as well as changes in the lining of the uterus.

Concerning the efficacy of Nexplanon, a chart is presented which, alas, reflects no more than a rudimentary notion of ranking contraceptive methods, and which cannot stand up to the standards of the most widely recognized ratings and rankings developed by Contraceptive Technology,[12] the World Health Organization (WHO),[13] the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),[14] and research on the safety of contraceptive methods [15]. In contrast to the latter research which ranks contraceptive methods according to safety, the chart presented by the manufacturer of Nexplanon does not contain any information on this parameter which, in the opinion of this author, is of utmost importance to most women. In addition, only 12 methods are mentioned, ie, 50 per cent of the methods contained in the Contraceptive Failure Table of Contraceptive Technology [12], [Table 3-2] and less than 50% contained in the WHO chart [13].

Concerning allergies, the manufacturer correctly warns prospective users about allergies to numbing medicines, ie, anesthetics and those used to clean the skin, ie, antiseptics. ‘‘These medicines will be used when the implant is placed into or removed from your arm’’. Concerning side effects reference is made to studies showing that ‘‘one out of ten women stopped using the implant because of an unfavorable change in their bleeding pattern’’ [11]

Regarding problems with insertion and removal it is specified that infection and ‘‘scarring, including a thick scar called a keloid around the insertion site’’ might occur. The possibility of expulsion is explained in terms of ‘‘coming out’’: ‘‘The implant may come out by itself. You may become pregnant if the implant comes out by itself’’. In explaining the risk of an ectopic pregnancy, the manufacturer appropriately mentions the possibility of a lethal outcome. ‘‘Ectopic pregnancy is a medical emergency that often requires surgery. Ectopic pregnancies can cause serious internal bleeding, infertility, and even death’’ [11].

In the same vein, the death-bearing sequelae of serious blood clots are mentioned ‘‘It is possible to die from a problem caused by a blood clot, such as a heart attack or a stroke’’[11]. And in this context examples of serious blood clots are cited, such as deep vein thrombosis located in the legs, pulmonary embolism located in the lungs, stroke located in the brain, heart attack, and total or partial blindness afflicting the eyes [11]. Additionally, the recommendable advice is given to quit smoking.

Consultation of the physician is recommended in case of the following conditions: pain in the lower leg that persists, severe or sharp chest pain or heaviness felt in the chest; sudden shortness of breath or coughing blood; symptoms of a severe allergic reaction such as swelling of face, tongue or throat; trouble breathing or swallowing; sudden severe headache which is different from usual headaches; weakness or numbness in the arm or leg, or trouble speaking; sudden partial or complete blindness (indicative of a cerebrovascular event); yellowing of skin or whites of the eyes, especially in conjunction with fever, tiredness, loss of appetite, dark colored urine, or light colored bowel movements (indicative of a liver disease); severe pain, swelling, or tenderness in the lower stomach or abdomen; lump in the breast; problems sleeping, lack of energy, tiredness, feeling of sadness (indicative of depressed mood); and intense menstrual bleeding.

Concerning breast feeding, the manufacturer explicates that ‘‘A small amount of the hormone contained in NEXPLANON passes into your breast milk. The health of breast-fed children whose mothers were using the implant has been studied up to 3 years of age in a small number of children. No effects on the growth and development of the children were seen’’ [11].

As can be seen from the FDA-Approved Patient Labeling discussed above lacunae still exist and this might be the reason the manufacturer recommends repeated consultation of the physician or contact with the company itself. Despite the manufacturer's offer to provide assistance, users should not rely solely on such offers because in some instances, health agencies such as the WHO have to intervene to warn the consumer about potential complications and risks. Thus, the WHO has issued rare reports of complications regarding Nexplanon, in particular migration from insertion site: ‘‘The MHRA has issued a warning about rare reports of complications with etonogestrel (Nexplanon) contraceptive implants. In rare cases, such implants have moved from the insertion site and reached the lung via the pulmonary artery. An implant that cannot be palpated at its insertion site in the arm should be located as soon as possible and removed at the [16] earliest opportunity. If an implant cannot be located within the arm, chest imaging should be performed. Correct subdermal insertion reduces the risk of these events’’[16].

As can be seen, the WHO had to intervene to inform the consumer about risks not mentioned by the manufacturer of the implants Nexplanon and Implanon. Incompleteness of the manufacturer's Patient Information Leaflet must therefore be assumed by the consumer despite numerous precautions and warnings appropriately discussed. Pertaining to risks the manufacturers mentions correctly the possibility of death in the case of ectopic pregnancy and in association with blood clots. There are, of course, areas in which important information is missing due to a lack of pertinent studies, as for example in special populations with hepatic disease or renal impairment. In addition, the consumer might be irritated by the speculative assumption in case of the most important issues of contraception, namely safety and efficacy. If safety and efficacy is in fact established for women of child-bearing age -- the manufacturer provides no reliable data -- it seems ethically unjustified to warrant safety and efficacy also for younger women. Equally disturbing for the reader is the use of an euphemistic nomenclature which uses the terminology ‘‘insert’’ and ‘‘insert-site’’ when in fact the procedure is an implantation, ie, substantially more risk-ful than an insertion of a diaphragm into the vagina. Vagueness of terminology is a weakness also of the FDA-Approved Patient Labeling where the size of the device is compared to a matchstick: ‘‘The implant is a flexible plastic rod about the size of a matchstick that contains a progestin hormone called etonogestrel’’ [11]. As matchsticks come in different sizes the consumer might prefer measurements in terms of international units. On a general note, the question must be raised as to whether or not each consumer reading the Patient Information Leaflet will pay sufficient attention to some important risks and potential complications, which are not always sufficiently underscored.

Intrauterine Devices:

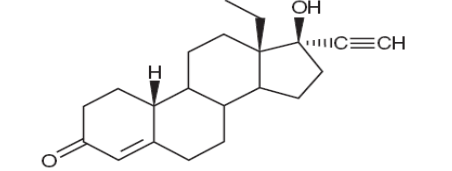

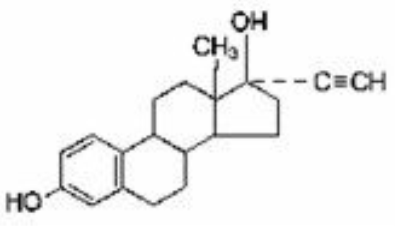

Besides implants, intrauterine devices are considered as belonging to LARC by most authors. Two kinds of intrauterine devices are in use, namely copper-containing and levonorgestrel- containing. The intrauterine device releasing levonorgestrel is marketed as Mirena (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) by one of the largest German pharmaceutical companies, which provides information in a 36-page document [10]. As regards clinical pharmacology, the device is intended to provide an initial release rate of 20 μg/day of levonorgestrel [10]. Levonorgestrel USP, (-)-13-Ethyl-17-hydroxy-18,19-dinor-17α-pregn-4-en-20-yn-3-one, the active ingredient in Mirena, has a molecular weight of 312.4, a molecular formula of C21H28O2, and the following structural formula (Figure 2 ):

|

Figure 2: Levonorgestrel. |

According to the manufacturer low doses of levonorgestrel can be administered into the uterine cavity with the Mirena intrauterine delivery system. Initially, levonorgestrel is released at a rate of approximately 20 μg/day. This rate decreases progressively to half that value after 5 years.

Mirena has mainly local progestogenic effects in the uterine cavity. Morphological changes of the endometrium are observed, including stromal pseudodecidualization, glandular atrophy, a leukocytic infiltration and a decrease in glandular and stromal mitoses. Studies of Mirena prototypes have suggested several mechanisms that prevent pregnancy, namely thickening of cervical mucus (which prevents passage of sperm into the uterus), inhibition of sperm capacitation or survival, and alteration of the endometrium [10].

Regarding clinical pharmacokinetics, the initial release of levonorgestrel into the uterine cavity subsequent to insertion of Mirena is 20 μg/day. A stable plasma level of levonorgestrel of 150-200 pg/mL occurs after the first few weeks after insertion of Mirena. Levonorgestrel levels after long-term use of 12, 24, and 60 months were 180 (plus-minus 66) pg/mL, 192 (plus-minus 140) pg/mL, and 159 (plus-minus 59) pg/mL, respectively. The plasma concentrations achieved by Mirena are lower than those seen with levonorgestrel contraceptive implants and with oral contraceptives. Unlike oral contraceptives, plasma levels with Mirena do not display peaks and troughs [10].

In serum, levonorgestrel is mainly bound to proteins (primarily to sex hormone binding globulin) and is metabolized to a large number of inactive metabolites. Metabolic clearance rates can differ among individuals considerably, and this might be the reason for significant individual variations in levonorgestrel concentrations seen in women using levonorgestrel–containing contraceptive products. ‘‘The elimination half-life of levonorgestrel after daily oral doses is approximately 17 hours; both the parent drug and its metabolites are primarily excreted in the urine’’ [10].

As contraindications the manufacturer lists the following: pregnancy or suspicion of pregnancy, congenital or acquired uterine anomaly including fibroids (if they distort the uterine cavity), acute pelvic inflammatory disease or a history of pelvic inflammatory disease (unless there has been a subsequent intrauterine pregnancy), postpartum endometritis or infected abortion in the past 3 months, known or suspected uterine or cervical neoplasia (or unresolved), abnormal Pap smear, genital bleeding of unknown etiology, untreated acute cervicitis or vaginitis (including bacterial vaginosis or other lower genital tract infections until infection is controlled), acute liver disease or liver tumor (benign or malignant), conditions associated with increased susceptibility to pelvic infections, a previously inserted IUD that has not been removed, hypersensitivity to any component of the product, and ‘‘known or suspected carcinoma of the breast’’[10].

Warnings issued by the manufacturer pertain to ectopic pregnancy, intrauterine pregnancy, sepsis, pelvic inflammatory disease, embedment and perforation. Concerning ectopic pregnancy loss of fertility is emphasized. Regarding intrauterine pregnancy, the manufacturer specifies: ‘‘In patients becoming pregnant with an IUD in place, septic abortion—with septicemia, septic shock, and death—may occur’’[10].

Particular emphasis is placed on group A streptococcal sepsis. ‘‘As of September 2006, 9 cases of Group A streptococcal sepsis (GAS) out of an estimated 9.9 million Mirena users had been reported. In some cases, severe pain occurred within hours of insertion followed by sepsis within days’’ [10]. Since death due to GAS is more likely when there is a delay in the treatment the manufacturer recommends alertness with respect to these serious infections albeit they are rare. ‘‘Aseptic technique during insertion of Mirena is essential. GAS sepsis may also occur postpartum, after surgery, and from wounds’’ [10].

With respect to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), death-bearing complications are appropriately mentioned by the manufacturer. ‘‘ . . .PID can cause tubal damage leading to ectopic pregnancy or infertility, or infrequently can necessitate hysterectomy, or cause death’’[10]. For the treatment of a PID the manufacturer provides appropriate guidelines and states that subsequent to the initiation of antibiotic therapy removal of Mirena might be indicated: ‘‘Removal of Mirena after initiation of antibiotic therapy is usually appropriate. Guidelines for PID treatment are available from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia.’’ [10].

Also, special attention is drawn to infection with actinomycetes, including the problem of false positive findings. ‘‘However, the management of the asymptomatic carrier is controversial because actinomycetes can be found normally in the genital tract cultures in healthy women without IUDs. False positive findings of actinomycosis on Pap smears can be a problem. When possible, confirm the Pap smear diagnosis with cultures’’ [10].

Concerning embedment, removal of Mirena is suggested, which might necessitate surgical intervention’’[10]. Pertaining to perforation or penetration the manufacturer specifies that the uterine wall or cervix might be affected and surgery indicated. ‘‘Mirena must be located and removed; ‘‘surgery may be required’’[10]. If detection of perforation or penetration is delayed, serious conditions may result, such as ‘‘migration outside the uterine cavity, adhesions, peritonitis, intestinal perforations, intestinal obstruction, abscesses and erosion of adjacent viscera’’ [10].

Concerning expulsion, the manufacturer specifies that bleeding or pain may indicate partial or complete expulsion. As regards ovarian cysts, it is explained that atresia of the follicle can be delayed so that the growth of the follicle continues. In approximately 12 per cent of the women using Mirena enlarged follicles have been found. Concerning breast cancer the manufacturer claims that no increased risk could be revealed by studies. ‘‘Two observational studies have not provided evidence of an increased risk of breast cancer during the use of Mirena’’ [10].

As can be seen from the above analysis, the manufacturer provides extensive information on various risks and potential complications. In particular, attention is drawn appropriately to death due to intrauterine pregnancy, due to group A streptococcal sepsis, and due to pelvic inflammatory disease. What remains unresolved, however, is the question as to whether nomenclature used in this information is comprehensible for the average consumer. Not all consumers might be sufficiently educated to know that sperm capacitation refers to the fact that ‘‘the capacity of sperm to produce fertilization is further enhanced if they spend some additional time in the female reproductive tract’’[17]. Along the same line, not all readers will be familiar with the nomenclature ‘‘stromal pseudodecidualization’’ and know that ‘‘decidua’’ designates ‘‘the endometrium of pregnancy, which is cast off at parturition’’ [8].

In view of the numerous precautions and warnings issued by the manufacturer of the intrauterine device Mirena and the implant Nexplanon discussed above, the consumer wonders why the scholarly literature on Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) only sporadically draws attention to serious adverse events and potential complications, including death-bearing conditions. In fact, one of the most noteworthy studies (2017) on LARC claims that ‘‘almost all women can safely use IUDs;’’[18] and the authors conclude by suggesting global dissemination of their findings: ‘‘All adolescents and adult women should be informed about the availability of LARC methods, given their extremely high effectiveness, safety, and high rate of continuation’’[18].

This emphasis on the safety of LARC comes as a surprise to many a reader because four years previously to the publication of 2017, authors of a study devoted to the intrauterine device Gynefix had criticized the conventional devices by enumerating numerous adverse events caused by them. On the basis of evidence-based research the authors indicated ‘‘increased expulsion rates, complaints of pain and erratic or increased menstrual bleeding, and subsequent high rates of discontinuation” [19] in association with the ‘‘conventional” devices hailed for their safety in the publication of 2017. To remedy the harm encountered by users of intrauterine devices a new device, marketed as Gynefix, was introduced into the market by a Belgian manufacturer. In its Information for the User (Information destinée aux utilisatrices) the manufacturer of Gynefix draws attention to the difference between older devices and its own product:” However older intrauterine devices (IUDs) were not favoured by women, many of whom complained of pain, discomfort, heavy bleeding and unintended expulsion in use. The new generation GyneFix® has been specially designed to be virtually trouble free whilst maintaining the superior levels of reliability, ease of use and spontaneity in relationships which women and their partners welcome” [20]. The precarious claim that Gynefix is ‘‘trouble free” has been disapproved, alas, already in 2002 when British authors published as study on cases of perforation associated with the use of Gynefix [21].

In light of such contradictory statements it is important that the consumer be critical in the face of claims made not only by manufacturers but also by research on contraceptive products -- which is frequently adulterated by conflicts of interest. A critical attitude is in place also for research on one of the most convenient forms of contraception, namely emergency or better post-coitus contraception.

Post-coitus (Emergency) Contraception

At present there seems to exist sufficient evidence to claim that Emergency Contraception (EC) can be considered as one of the most convenient forms of birth control, especially for women with diminishing sexual activity. After all, it requires administration of pills only twice within 12 hours and thus avoids the burden of daily administration. In addition, it does not require assistance by a physician. Several forms of EC have been described in the literature, namely oral administration of ulipristal acetate, oral administration of standard contraceptive pills, and intrauterine devices [22].

Concerning efficacy, the antiprogestin ulipristal acetate (30 mg in a single dose) is regarded as the most effective pill for EC in the US and in Europe, ‘‘with reported estimates of effectiveness ranging from 62% to 85%’’ [22]. If intrauterine devices are employed for EC, the efficacy is even higher, ie, 0.2 (perfect and typical use) for Mirena (levonorgestrel); 0.6 (perfect uses) and 0.8 (typical use) for ParaGard (copper T) [12].

Ulipristal acetate:

Information on ulipristal acetate is provided at least by two prominent manufacturers, namely the manufacturer of Esmya, [23] offering a 27-page document, and the manufacturer of ella, [24] offering an 11-page document. The former describes a 5 mg tablet used for the treatment of fibroids, either pre-operatively or intermittently. ‘‘Ulipristal acetate is indicated for pre-operative treatment of moderate to severe symptoms of uterine fibroids . . . for intermittent treatment of moderate to severe symptoms of uterine fibroids in adult women of reproductive age’’ [23]. Concerning posology, the manufacturer specifies that the treatment, which may last up to 3 months, should be initiated subsequent to menstruation and consist of one tablet of 5 mg to be administered daily.

The manufacturer of ella specifies that its product is indicated for the prevention of pregnancy subsequent to unprotected coitus: ‘‘ella is a progesterone agonist/antagonist emergency contraceptive indicated for prevention of pregnancy following unprotected intercourse or a known or suspected contraceptive failure. ella is not intended for routine use as a contraceptive’’ [24].

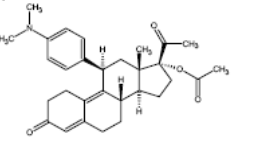

In the description, the manufacturer specifies that the ulipristal acetate-containing tablet ella is for oral use and contains 30 mg of a single active steroid ingredient, namely ulipristal acetate, which is a synthetic progesterone agonist/antagonist [17alpha acetoxy-11beta-(4-N,N-dimethylaminophenyl)-19-norpregna-4,9-diene-3,20-dione]. Among the inactive ingredients are ‘‘lactose monohydrate, povidone K-30, croscarmellose sodium and magnesium stearate’’ [24]. The structural formula (Figure 3) is the following:

|

Figure 3: Ulipristal acetate (C30H37NO4). |

In discussing the clinical pharmacology, the manufacturer explains that the likely primary mechanism of action for emergency contraception is ‘‘inhibition or delay of ovulation; however, alterations to the endometrium that may affect implantation may also contribute to efficacy’’ [24]. Pertaining to pharmacodynamics, it is stated that Ulipristal acetate is a selective progesterone receptor modulator with antagonistic and partial agonistic effects (a progesterone agonist/antagonist) at the progesterone receptor.

The pharmacodynamics of ulipristal acetate, the manufacturer specifies, depends on the phase of the menstrual cycle in which the pill is administered. ‘‘Administration in the mid-follicular phase causes inhibition of folliculogenesis and reduction of estradiol concentration. Administration at the time of the luteinizing hormone peak delays follicular rupture by 5 to 9 days. Dosing in the early luteal phase does not significantly delay endometrial maturation but decreases endometrial thickness by 0.6 ± 2.2 mm (mean ± SD)’’ [24].

Concerning pharmacokinetics absorption and plasma concentrations are explained: ‘‘Following a single dose administration of ella in 20 women under fasting conditions, maximum plasma concentrations of ulipristal acetate and the active metabolite, monodemethyl-ulipristal acetate, were 176 and 69 ng/ml and were reached at 0.9 and 1 hour, respectively’’ [24]. Concerning distribution it is explained that ulipristal acetate is ‘‘highly bound (> 94%) to plasma proteins, including high density lipoprotein, alpha-l-acid glycoprotein, and albumin’’ [24]. Ulipristal acetate is metabolized to two metabolites, namely mono-demethylated and di-demethylated. Regarding excretion, it is stated that ‘‘the terminal half-life of ulipristal acetate in plasma following a single 30 mg dose is estimated to 32.4 ± 6.3 hours’’ [24].

Besides ulipristal acetate as one of the most recently advocated options for EC, there are of course other pills available, and they can be divided into three types, namely combined ECPs containing both estrogen and progestin; progestin-only ECPs; and ECPs which contain an antiprogestin (either ulipristal acetate or mifepristone). According to a publication of 2017, progestin-only ECPs have replaced the older combined ECPs ‘‘because they are more effective and cause fewer side effects’’[22].

Concerning efficacy, attention must be drawn to the WHO table of 2017 which indicates an estimate of 99% efficacy by explaining: ‘‘If all 100 women used progestin-only emergency contraception, one would likely become pregnant’’[13] In the same vein, German research argued as early as 2000 that the efficacy of Emergency Contraception by means of ‘‘interceptive pills’’ in case of perfect use is as effective as 99% [25]. The latter research, which ranks contraceptive methods according to the Pearl Index (PI), explains that the morning-after-pill interrupts the synchronisation between blastocyst development and endometrial preparedness for nidation. According to this rather outdated research, the 4 pills used for interception (50 μg ethinyl estradiol and 0.25 mg levonorgestrel) are taken within 60 hours: 2 are taken within 48 hours of unprotected cohabitation and the remaining 2 are taken after an interval of 12 hours.

Strangely enough, efficacy specified in 2000 by German authors and the WHO estimate of 2017 do not harmonize with the estimate presented by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in a survey of contraceptive methods [14]. This survey, which appeared in 2013, indicates 85% efficacy in case of perfect use and 87.5% efficacy in case of typical use – which is described as ‘‘7 out of 8 women would not get pregnant after using Emergency Contraceptives’’. What confuses the reader of the FDA survey are the estimates which indicate that typical use (87.5%) would be more effective than perfect use (85%). Furthermore, the reader of the FDA survey seeks in vain information on non-hormonal, ie, fertility awareness-based (periodic abstinence) methods.

In addition to pills, intrauterine devices are suitable for EC, namely a Copper T intrauterine contraceptive (IUC), and a levonorgestrel-releasing IUC. The copper-containing IUC (ParaGard) is a non-hormonal device and contains 380 mm2 of copper around the arms and stem. ‘‘The copper-containing IUD releases copper ions that are toxic to sperm’’[18].

The levonorgestrel-releasing (non-copper) intrauterine system (sold as Mirena in the U.S.) has been described comprehensively by the manufacturer in a consumer leaflet. The device consists of a T-shaped frame (T-body) made out of polyethylene and a steroid reservoir (hormone elastomer core) around the vertical stem. ‘‘The T-body is 32 mm in both the horizontal and vertical directions. The polyethylene of the T-body is compounded with barium sulfate, which makes it radiopaque. A monofilament brown polyethylene removal thread is attached to a loop at the end of the vertical stem of the T-body’’[10].

Pills used for EC:

Originally, pills for EC have been known also under the designation ‘‘morning-after-pill’’ [25]. This label, despite its wide use, is inappropriate since ECPs may be initiated earlier than the morning after, ie, immediately after unprotected intercourse -- the sooner the better, but within 120 hours.

Combined ECPs contain the hormones estrogen and progestin. The estrogen ethinyl estradiol and the progestin levonorgestrel or norgestrel (which contains two isomers, only one of them being bioactive, ie, levonorgestrel) have been studied extensively in clinical trials, according to a study of 2017 [22]. With respect to these hormones it has been noted that products dedicated as EC, ie, specially packaged for use as EC, are not the only ones that can be used. In fact, certain ordinary birth control pills in specified combinations are also effective as emergency contraception. The regimen is one dose followed by a second dose 12 hours later, where each dose consists of 4, 5, or 6 pills, depending on the brand. As of 2017, 26 brands of combined oral contraceptives were approved in the US for use as emergency contraception. ‘‘Research has demonstrated the safety and efficacy of an alternative regimen containing ethinyl estradiol and the progestin norethindrone; . . . this result suggests that oral contraceptive pills containing progestins other than levonorgestrel may also be used for emergency contraception’’ [22].

In studies on dosage of levonorgestrel it could be found that administration of a single dose proved to be equally effective. ‘‘However, studies have shown that a single dose of 1.5 mg is as effective as two 0.75 mg doses 12 hours apart’’. One of these studies showed no difference between the two regimens regarding adverse events, ‘‘while the other found greater levels of headache and breast tenderness (but not other side effects) among study participants taking 1.5 mg of levonorgestrel at once’’ [22].

Concerning marketing, it has been stated that by 2017 levonorgestrel was marketed internationally increasingly in a one-dose formulation (one 1.5 mg pill) rather than the two-dose formulation (two 0.75 mg tablets, taken 12 hours apart) [22].

Antiprogestins (Ulipristal acetate, mifepristone, COX2-inhibitor):

Ulipristal acetate (30 mg in a single dose), considered a second-generation antiprogestin, entails according to some authors no noteworthy discomfort and is well-tolerated besides being highly effective. ‘‘The second-generation antiprogestin ulipristal acetate (30 mg in a single dose) has been studied for use as emergency contraception and has been found to be highly effective and well-tolerated’’ [22].

Mifepristone:

Another antiprogestin, mifepristone, has also been studied for use as an emergency contraceptive pill.[22,p.2] Mifepristone, considered a first-generation progesterone receptor modulator, is approved in several countries for early first-trimester medication abortion. ‘‘Mifepristone has been shown to be highly effective for use as emergency contraception, with few side effects (delayed menstruation following the administration of mifepristone is one notable side effect)’’ [22]. As of 2017, its availability was limited to Armenia, Moldova, Ukraine, China, Russia, and Vietnam.

COX-2 inhibitor:

The COX-2 inhibitor Meloxicam is considered an effective emergency contraceptive measure if 30 mg are administered for five consecutive days during the late follicular phase and has no bearing on the endocrine status. ‘‘This regimen does not alter the endocrine profile of the cycle and causes no menstrual disturbance’’ [22]. On the other hand, the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib has been considered as not possessing a potential for emergency contraception.

As can be seen from the above survey of pills for EC, ongoing studies lead to new insights on their dosage and administration. The most important insights are the absence of harm in case of repeated use of ECPs and the possibility of administering one larger dose once in lieu of two smaller doses twice.

Concerning mechanism of action the important claim has been made that there is no abortogenicity associated with levonorgestrel. ‘‘Levonorgestrel does not impair the attachment of human embryos to an in vitro endometrial construct and has no effect on the expression of endometrial receptivity markers’’ [22]. The claim made in favor of levonorgestrel is also made for ECPs in general, but its validity depends on the definition of pregnancy. ‘‘ECPs do not interrupt an established pregnancy, defined by medical authorities such as the United States Food and Drug Administration/National Institutes of Health and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists as beginning with implantation. Therefore, ECPs are not abortifacient’’ [22].

In contrast to this claim, physiological research holds that the question of abortogenicity is by no means resolved so that the problem discussed already during the 20th century is being perpetuated. ‘‘The synthetic steroid mifepristone (RU-486) binds to the receptor but does not release the heat shock protein, and it blocks the binding of progesterone. Since the maintenance of early pregnancy depends on the stimulatory effect of progesterone on endometrial growth and its inhibition of uterine contractility, mifepristone causes abortion. In some countries mifepristone combined with a prostaglandin is used to produce elective abortions’’[17].

The question of abortogenicity is of course also addressed by the manufacturer of ulipristal acetate in the ‘‘Patient Counseling Information’’ [24]. It is considered only a possible mechanism of action, while the primary mechanism concerns the release of an ovum. ‘‘ella is thought to work for emergency contraception primarily by stopping or delaying the release of an egg from the ovary. It is possible that ella may also work by preventing attachment (implantation) to the uterus’’ [22].

It should be noted also that the Highlights of Prescribing Information, Full Prescribing Information and FDA Approved Patient Labeling/Patient Counseling Information furnished by the manufacturer Ella contain no more than 11 pages and provide only limited information. Thus, concerning ectopic pregnancy, the patient information leaflet makes no mention of the possibility of severe threats to the health of the user. Moreover, regarding liver and renal impairment no data can be furnished as there are no studies available. ‘‘No studies have been conducted to evaluate the effect of hepatic disease on the disposition of ella. . . . No studies have been conducted to evaluate the effect of renal disease on the disposition of ella’’ [24].

Combined oral contraceptives

In the past, combined oral contraceptives were the most widely used form of contraception, but with the appearance of implants and refined IUD-systems, this prevalence apparently has already changed.

Norethindrone/Ethinyl estradiol containing tablets [26]: norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol (Ortho-Novum and Modicon).

The chemical name for norethindrone is 17-Hydroxy-19-nor-17α-pregn-4-en-20-yn-3-one, and for ethinyl estradiol 19-Nor-17α-pregna-1,3,5(10)-trien-20-yne-3,17-diol [26]. Their structural formulas (Figure 4 and 5 ) are as follows:

|

Figure 4: Norethindrone. |

|

Figure 5: Ethinyl estradiol. |

Concerning clinical pharmacology, the manufacturer explains that combined oral contraceptives act by suppressing gonadotropin secretion. Although the primary mechanism of this action is inhibition of ovulation, other alterations are effected also, such as changes in the cervical mucus (which increase the difficulty of sperm entry into the uterus) and the endometrium (which reduce the likelihood of implantation).

Concerning contraindications, the manufacturer lists thrombophlebitis or thromboembolic disorders; a past history of deep vein thrombophlebitis or thromboembolic disorders; known thrombophilic conditions; cerebral vascular or coronary artery disease (current or history); valvular heart disease with complications, persistent blood pressure values of 160 mm Hg (or higher) systolic and 100 mg Hg (or higher) diastolic; diabetes with vascular involvement; headaches with focal neurological symptoms; major surgery with prolonged immobilization; known or suspected carcinoma of the breast; carcinoma of the endometrium or other known or suspected estrogen-dependent neoplasia; undiagnosed abnormal genital bleeding; cholestatic jaundice of pregnancy or jaundice with prior pill use; acute or chronic hepatocellular disease with abnormal liver function; hepatic adenomas or carcinomas; known or suspected pregnancy; hypersensitivity to any component of the product. The manufacturer also states that the use of oral contraceptives is associated with increased risks of myocardial infarction, thromboembolism, stroke, hepatic neoplasia, and gallbladder disease.

Concerning thromboembolism, the manufacturer correctly calls to mind that risks are well established. ‘‘An increased risk of thromboembolic and thrombotic disease associated with the use of oral contraceptives is well established’’ [26].

The manufacturer also takes pain to underline the importance of certain conditions, such as hypertension, and of the users' life style. ‘‘In a large study, the relative risk of thrombotic strokes has been shown to range from 3 for normotensive users to 14 for users with severe hypertension. The relative risk of hemorrhagic stroke is reported to be 1.2 for non-smokers who used oral contraceptives, 2.6 for smokers who did not use oral contraceptives, 7.6 for smokers who used oral contraceptives, 1.8 for normotensive users and 25.7 for users with severe hypertension. The attributable risk is also greater in older women’’ [26].

Concerning carcinomas of the reproductive organs and the breast, the manufacturer specifies that there might be a slightly increased risk of breast cancer risk ‘‘among current and recent users of COCs’’ [26]. There is also a reference to studies suggesting ‘‘that oral contraceptive use has been associated with an increase in the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in some populations of women’’ [26].

Concerning hepatic adenomas, reference is made to statistical data, and the possibility of lethal sequelae is appropriately mentioned: ‘‘Indirect calculations have estimated the attributable risk to be in the range of 3.3 cases/100,000 for users’’. This risk, according to the manufacturer, increases after four or more years of use, above all in cases where oral contraceptives of higher dose are administered. ‘‘Rupture of benign, hepatic adenomas may cause death through intra-abdominal hemorrhage’’ [26].

Adverse reactions associated with the use of oral contraceptives include thrombophlebitis and venous thrombosis with or without embolism, arterial thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, cerebral hemorrhage, cerebral thrombosis, hypertension, gallbladder disease, hepatic adenomas or benign liver tumors. Evidence of an association is assumed for the use of oral contraceptives and mesenteric thrombosis as well as retinal thrombosis. Concerning fat metabolism the manufacturer states: ‘‘A small proportion of women will have persistent hypertriglyceridemia while on the pill’’ [26].

The manufacturer lists also adverse reactions ‘‘that have been reported in patients receiving oral contraceptives and are believed to be drug-related’’ [26]: nausea, vomiting gastrointestinal symptoms (such as abdominal cramps and bloating), breakthrough bleeding, spotting, change in menstrual flow, amenorrhea, temporary infertility after discontinuation of treatment, edema, melasma which may persist, breast changes (tenderness, enlargement, secretion), change in weight (increase or decrease), change in cervical erosion and secretion, diminution in lactation when given immediately postpartum, cholestatic jaundice, migraine, allergic reaction (including rash, urticaria, angioedema), mental depression, reduced tolerance to carbohydrates, vaginal candidiasis, change in corneal curvature (steepening), and intolerance to contact lenses.

Listed are also adverse reactions that have been reported in users of oral contraceptives where a causal relationship has been neither confirmed nor refuted, such as: pre-menstrual syndrome, cataracts, changes in appetite, cystitis-like syndrome, headache, nervousness, dizziness, hirsutism, loss of scalp hair, erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, hemorrhagic eruption, vaginitis, porphyria, impaired renal function, hemolytic uremic syndrome, acne, changes in libido, colitis, and Budd-Chiari Syndrome [26].

As can be seen from the above analysis, the manufacturer of Ortho Novum pills presents extensive information and appropriately mentions the possibility of death due to rupture of hepatic adenomas. Similar information is provided by other manufacturers of oral contraceptive pills such as for levonorgestrel and ethinyl estradiol containing tablets (Allesse), [27] for desogestrel/ethinyl estradiol and ethinyl estradiol containing tablets (Mircette), [28] and for the minipill [29].

The manufacturer of Alesse provides 44 pages to inform the consumer about the 28 tablets containing levonorgestrel and ethinyl estradiol, namely 7 light-green inert tablets and 21 pink active tablets each containing 0.10 mg of levonorgestrel (an entirely synthetic progestogen) and 0.2 mg of ethinyl estradiol, ie, d(-)-13β-ethyl-17α-ethinyl-17β-hydroxygon-4-en-3-one (progestogen) and 17α-ethinyl-1,3,5(10)-estratriene-3, 17β-diol (ethinyl estradiol).[27,p.1]

Concerning hepatic adenomas the possibility of death is mentioned due to rupture. ‘‘Rupture of rare, benign, hepatic adenomas may cause death through intraabdominal hemorrhage’’ [27]. Noteworthy is the manufacturer's warning about sexually transmitted diseases for which pills or devices --- except condoms -- do not provide protection. ‘‘Oral contraceptives do not protect against transmission of HIV (AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) such as chlamydia, genital herpes, genital warts, gonorrhea, hepatitis B, and syphilis.’’ And in this context, it is warned about death to due to disease: ‘‘But there are some women who are at high risk of developing certain serious diseases that can be life-threatening or may cause temporary or permanent disability or death’’ [27].