Research Article

Does High Continuity of Care Reduce Preventable Hospitalization Among Patients with Mental Illness?

Yang Wang1, Shou-Hsia Cheng2* and Li-Wu Chen3

1Joseph J Zilber School of Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

2Institute of Health Policy and Management, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

3Department of Health Services Research and Administration, College of Public Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA

*Corresponding author: Shou-Hsia Cheng, Institute of Health Policy and Management, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, Tel: +886 233668057; E-mail: shcheng@ntu.edu.tw

Citation: Wang Y, Shou-Hsia Cheng, Li-Wu Chen (2017) Does High Continuity of Care Reduce Preventable Hospitalization Among Patients with Mental Illness? J Glob Epidemiol Environ Health 2017: 1-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.29199/2637-7144/GEEH-101013

Received: 12 July, 2017; Accepted: 25 August, 2017; Published: 12 September, 2017

Abstract

Purpose: Preventable hospitalization poses an extremely heavy financial burden on health care systems of many countries. Patients with mental illness may not be able to comply with physicians’ recommendations on medications and regular visits, which possibly results in those preventable hospital admissions. This study aimed to investigate how mental illness may modify the effect of continuity of care on patients’ experiencing preventable hospitalization.

Methods: We used Taiwan longitudinal National Health Insurance Research Database to examine differences in effects of continuity of care on preventable hospitalization between patients with and without mental illness. The main outcome was whether a beneficiary had preventable hospital admissions. We chose Continuity of Care Index (COCI) to measure our key explanatory variable. Other covariates included mental illness, time-variant variables (age, outpatient visits in the previous year, inpatient visits in the previous year, low-income status, primary source of care, Charlson index score), time-invariant variable (sex), and dummy variables for hospital geographic location. Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models were applied to assess the relationship between continuity of care and preventable hospitalization among patients with and without mental illness, respectively.

Results: We found higher continuity of care protected patients without mental illness from preventable hospitalization. However, AORs increased towards the direction of null effect and became insignificant among mental patients.

Conclusion: Our study suggests that the effect of continuity of care on reducing preventable hospitalization may be compromised by mental illness. This highlights the importance of integrated health care delivery model with a multispecialty medical team.

Background

Preventable hospitalization is defined as hospital admissions attributable to Ambulatory Care-Sensitive Conditions (ACSCs) that would have been kept well under control in outpatient settings if patients had accessed high-quality primary care [1]. However, quality of care can be substantially jeopardized by multiple factors, for example, patients with mental illnesses may not be able to comply with physicians’ recommendations on medications and regular visits. Those hospital admissions pose an extremely heavy financial burden on health care systems of many countries [2-4]. From 2005 to 2010, total annual health costs due to preventable hospitalization among adult patients in the United States were over $30 billion [5]. To contain the associated costs, multiple initiatives thus have been launched with the aim to reduce preventable hospitalizations in the US, such as VA (United States Department of Veterans Affairs) Care Coordination Home Telehealth (CCHT) program, and CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) evidence-based interventions in nursing facilities [6,7].

Patient sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, mental status, health care access, and quality of care etc., have been found to be associated with preventable hospitalization [8-10]. A few prior studies have examined the effect of continuity of care, as a critical measure of primary care access, on reducing preventable hospital admissions, yielding very similar results that they are negatively correlated [11-14]. For example, Nyweide et al., found that a 0.1 increase in constructed indices for continuity of care led to a decrease in preventable hospitalization among older adults by 2 percent [14]. Cheng and colleagues analyzed health insurance claim data and observed impacts of continuous care on reducing preventable hospitalization to be all significant across three defined age groups [13].

Researchers have recently extended their interests to investigate if mental illness influences ACSC-related hospital admissions, given the fact that about 1 in 5 US adults are diagnosed with mental or emotional disorders [15]. Mai et al., conducted a retrospective cohort study and found patients with mental illnesses were twice more likely to experience avoidable hospital admissions than those without in Western Australia [10]. Another study using 2003-2008 HCUP National Inpatient Sample showed that Schizophrenia increased odds of preventable hospitalizations [16]. A prior study also documented poorer continuity of care among patients with major depression in primary care settings [17]. However, the dynamic relationships among mental illness, continuity of care, and preventable hospitalization still remain unknown. In particular, little research has investigated how mental illness may modify the effect of continuity of care on patients’ experiencing preventable hospitalization.

Thus, our objective is to examine differences in effects of continuity of care on preventable hospitalization between patients with and without mental illness. The prevalence of probable common mental disorders among adults increased from 11.5% to 23.8% between 1990 and 2010 in Taiwan [18]. We used Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) Claims data for this study. Taiwan implemented its mandatory NHI program in 1995, with 99% of its population covered. It aims to improve residents’ access to care in health care market where they can decide to seek services from either primary care physicians (also considered as a specialty in Taiwan) or specialists based on their symptoms. The contribution of our study is particularly significant in the context of Affordable Care Act, which also targets at increasing continuity of care by expanding insurance coverage and initiating innovative health care delivery models in the United States, such as patient-centered medical home. This study also provides critical insights into developing effective measures to tackle the problems of preventable hospitalization among patients with mental illness, eventually lowering medical costs and improving quality of care.

Methods

Data source

We used outpatient and inpatient components from Taiwan longitudinal National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to examine the effect of continuity of care on reducing preventable hospitalization stratified by mental illness status. The database covers a variety of detailed information on basic demographics, socioeconomic status, ICD-9-CM diagnoses codes, procedures, and medications. The 2005 NHI cohort that we used consisted of 25 subsets of 40,000 subjects, which were randomly selected from the entire enrollee sample to be nationally representative. The first 5 subsets in three panel years from 2006 to 2008 were used to form a study dataset of 200,000 beneficiaries. We started from the year 2006, rather than the baseline 2005, to avoid the fluctuation of health care utilization due to the prior outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in Taiwan. For each beneficiary, we were able to track all the health services covered by the NHI program from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2008, in both outpatient and inpatient settings.

Our study population was adults aged 18 and older. We applied three following exclusion criteria to select NHI beneficiaries for this study. First, subjects were excluded if they had any missing values in any of dependent and independent variables for all the three panel years between 2006 and 2008. Second, the calculation of Continuity of Care Index (COCI) is more meaningful and robust for subjects with more physician visits, so we followed previous studies and excluded beneficiaries who had fewer than three non-mental outpatient visits (based on primary diagnose code) in any of the panel years [11-13]. Third, we excluded mental patients who were not diagnosed with mental illnesses for all the three panel years from our study population and ended up with 2,034 patients with mental illness. To increase the balance of the sample sizes, and maximize efficiency [19], we matched 1 mental patient with 3 non-mental patients based on their age, sex, and hospital location (usual source of care) at the baseline year 2006. Our final sample size was 8,136, including 2,034 mental patients and 6,012 non-mental patients, and each subject contributed data for the subsequent 3 years.

Measures

Continuity of care

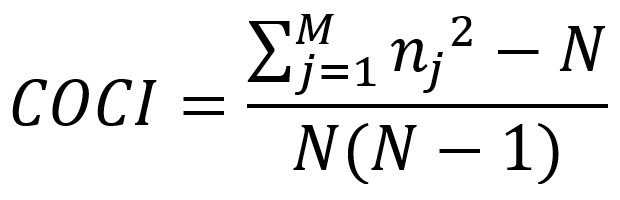

Our key explanatory variable was continuity of care. A few indexes were constructed to measure different dimensions of continuity of care in previous studies, such as density, dispersion, and sequence [20,21]. Considering the Taiwan healthcare market featuring physician-shopping behavior, we chose Continuity of Care Index (COCI) to gauge its dispersion, the extent to which patients would consistently go to see the same physician when healthcare needed. The COCI is a function of the number of different physicians seen and the number of visits to each physician. We calculated it for each subject by panel year following the formula given below:

where N is the total number of physician visits; nj, the number of visits to physician j; and M, the number of physicians throughout each panel year. To enhance the comparability of COCI, we included 4 types of non-traditional-Chinese medical visits in outpatient settings for the calculation, including common cases, chronic cases (excluding tuberculosis), prescription medication related to chronic diseases, and special cases. We also excluded visits related to mental illness. The COCI has a range from 0 to 1, with a greater value indicating better continuity of care.

Preventable hospitalization

The main outcome was whether a beneficiary had hospital admissions that could be potentially prevented by receiving high-quality outpatient care in each of the panel years from 2006 to 2008. It was dichotomized as none vs. at least one of those admissions. We identified preventable hospitalization according to the Prevention Quality Indicators (PQI) by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Thirteen medical conditions leading to preventable hospitalizations were included: Diabetes short-term complications, Diabetes long-term complications, Perforated appendix, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) or Asthma in older age, Hypertension, Heart failure, Dehydration, Bacterial pneumonia, Urinary tract infection, Angina without procedures, Uncontrolled Diabetes, Asthma in younger adults, and Lower-extremity amputation among patients with diabetes. All the information on patient diagnosis (International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification, ICD-9-CM) and procedure codes related to PQI was obtained from the inpatient component of NHI claims. Given that patients might need to visit different physician’s due to medical conditions or health care-seeking behaviors changing across time, we decided to measure the effect of continuity of care on preventable hospitalization in the same year [13].

Other covariates

We included enrollee demographics characteristics, socioeconomic status, geographic area and healthcare-seeking behavior as covariates, including age (in years), sex, low-income status, hospital location (Taipei, North, Middle, South, Gaoping, and East) and primary source of care (hospital vs. clinic). We also quantified health need by using following 3 indicators: outpatient visits in the previous year (times 0-10, 11-20, and 21 and above), inpatient visits in the previous year (none, once, and at least twice), and the Charlson index score (0, 1-2, and 3 and above). The Charlson index is a common measure for commodities when using health administrative databases for research, and it involves 17 groups of medical conditions defined by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes. Each condition is given a different weight score from 1 to 6, with a higher value being more severe [22].

We defined mental illness using principal diagnosis codes (ICD-9-CM) following a previous study conducted in Taiwan [23]. Although mental illnesses could be categorized into major and minor psychiatric disorders, we were not able to do this due to the limited sample size. Beneficiaries who had the principal diagnosis codes 290 through 298, 300 through 302, 306 through 311, or 316 were identified as patients with mental illness (Table A1). To increase its accuracy, for both comorbid (the Charlson index) and mental conditions, only diagnosis codes appearing at least 3 times in either outpatient or inpatient settings throughout each of the panel years were taken into consideration [13].

Analytical plan

We performed univariate analyses to characterize the distribution of all variables of interest and covariates, stratified by mental illness and panel year. The Pearson χ2 test was used to measure if differences in preventable hospitalization and continuity of care were significant between patients with and without mental illness within each panel year. We then used multivariate Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) models to examine the associations between preventable hospitalization and continuity of care for patients with and without mental illness, separately, to adjust for individual correlation in our sample. Because our outcome variable was binary, we used a logit link for GEE model [24]. Covariates in the model included time-variant variables (age, outpatient visits in the previous year, inpatient visits in the previous year, low-income status, primary source of care, Charlson index score), time-invariant variable (sex), and dummy variables for hospital geographic location. All the analyses were performed using statistical software STATA 13.0 SE (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). We considered a p-value less than 0.05 as statistical significant.

Results

Distributions of preventable hospitalization, continuity of care and other covariates by mental illness status and panel year are given in Table 1. Patients with mental illness were more likely to experience preventable hospitalization than those without mental illness consistently across panel years, and this disparity increased as the cohort of population was aging. For example, in 2006, probabilities of having preventable hospitalization among non-mental and mental patients were 2.03% vs. 2.90% (P-value=0.022), as compared to 2.82% vs. 4.47% in 2008. Patients with mental illness also tended to have poorer continuity of care measured by COCI. Of non-mental patients in 2006, 33.51% were categorized into high COCI group, but this proportion for mental patients was only 28.37%. This pattern persisted across panel years too.

Mental patients utilized more health care services than non-mental ones in both outpatient and inpatient settings. Approximately only 30% of non-mental patients had 21 or more times of outpatient visits in the previous year, while close to 50% of mental patients did. The Charlson index score was also higher for mental patients, indicating their multiple commodities and potential complex health needs. For example, they were 15% less likely than non-mental patients to have no commodity. In addition, mental patients had significantly higher odds of being from low-income households than non-mental patients (0.69% vs. 4.87% in 2006), and they were more likely to seek for health care in hospitals, rather than clinics, as their primary source of care.

Table 1: Distribution of Preventable Hospitalization and Characteristics for Adults Patients by Mental Illness and Panel Year, NHIRD 2006-2008. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

We then measured multivariate-adjusted associations between continuity of care and preventable hospitalization stratified by mental illness status, with Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR), 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and p-value reported (Table 2). For patients without mental illness, medium COCI (AOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.61-0.98) decreased the odds of their having preventable hospitalization by 23% with low COCI being the reference group, and high COCI had an even greater protective effect (AOR 0.61, 95% CI 0.47-0.79). In contrast, the impact of medium COCI was no longer significant among patients with mental illness. High COCI still had a potential protective effect, suggested by marginally significant AOR (0.69, 95% CI 0.48-1.02). However, both AORs increased towards the direction of null effect from non-mental to mental patients. We also did a sensitivity analysis using the continuous form of COCI, and results turned out to be similar, with AOR from 0.32 to 0.46 (Table A1). In addition, older age, higher volume of inpatient services utilized, low-income status, hospital as primary source of care, and multiple comorbidities were associated with higher probability of experiencing preventable hospitalizations in both groups of mental and non-mental patients.

Table 2: Multivariate-Adjusted Association Between Preventable Hospitalization and Continuity of Care from General Estimating Equation (GEE) Model, NHIRD 2006-2008. * P<.05, ** P<.01, *** P<.001 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discussions

Prior literature has shown that continuity of care in primary care settings has a significant impact on reducing preventable hospitalization among both general population and patients with specific medical conditions, such as diabetes and COPD [13,14,25-28]. To our knowledge, we are the first to examine the effects of continuity of care on hospital admissions due to ACS conditions among patients with and without mental illness. Our univariate results from Taiwan’s health insurance claim data show that beneficiaries with mental illness are at a significantly higher risk of having preventable hospitalization as compared to those without (e.g., 2.90% vs. 2.03% in 2006). This corroborates most previous research on the impact of mental conditions on ACSC-related hospital admissions [10,29-31]. For example, a retrospective cohort study in New York found that mental disorders increased odds of preventable hospitalization by 1.3 times (AOR 2.30, CI 2.17-2.43), indicating an even stronger effect of mental conditions than that in our study. This may be attributable to universal insurance coverage in Taiwan where patients have better access to care in general. However, there is also some exception, such as no association between preventable hospitalization and mental illness found in a study by Ajmera and colleagues [32]. This insignificant finding may be due to recall bias because they identified patients with mental conditions based on self-reported data.

Our study suggests two possible mechanisms through which mental conditions can affect preventable hospitalization. One is that patient with mental illness are more likely to have lower continuity of care in outpatient settings, which would increase the odd of preventable hospitalization. In our study, the beneficiaries without mental illness are more likely to have higher COCI than those with mental illness (e.g., the highest COCI groups: 33.51% vs. 28.37% in 2006). Druss et al., found a piece of similar evidence that patients with untreated major depression had a higher odd of reporting having changed usual source of care during the past 12 months, and seeking for routine services in an emergency room [17]. This could be partially explained by their relatively lower socioeconomic status as compared patients without mental illness. In a US study, depressed respondents were 1 time more likely to have no insurance and incomes below the federal poverty line than non-depressed ones [17]. We observed a larger difference that almost 5% of beneficiaries with mental illness are from low-income households, as compared to less than 1% of those without in Taiwan (4.87% vs. 0.69% in 2006). They even tend to have more complex comorbidities. Given those, financial stress due to high medical expenses would increase the possibility of delaying health care needed by patients with mental illness and eventually ending up with receiving care in an emergency department, especially in countries without universal health coverage like the US. In the Taiwan’s healthcare market, those patients may choose cheaper health care in clinics, rather than the same physician for treating their medical conditions.

The other possible mechanism suggested is that the effect of continuity of care on reducing preventable hospitalization is compromised by mental illness. In our study, higher COCI is associated with a decreased odd of preventable hospitalization among non-mental patients (AOR: medium COCI 0.77; high COCI 0.61), which is consistent with all the previous studies on the same topic [11-14]. However, among patients with mental illness, the AOR for medium COCI is not significant, and high COCI is only marginally significant with its magnitude also moving towards the direction of a smaller effect (AOR 0.69). Factors from both patient and provider side may contribute to this reduced impact of continuity of care. For example, patients with mental illness may have psychological and cognitive limitations that could deter effective communication [33,34], which may further jeopardize interpersonal trusts between them and physicians. Evidence also showed that they tend to have poorer compliance with treatment recommended by physicians [35]. For providers, primary care physicians may misdiagnose medical conditions, given a lack of sufficient knowledge about mental illnesses [29]. Other unpleasant experiences that might happen to those patients in health care facilities were also reported, such as provider bias and patient stigma [33-36]. All of these can be barriers to treatment processes, which would result in preventable hospitalization among the patients even if they have an acceptable level of continuity of care. Considering this, our study supports the integrated health care model with both psychiatrist and primary care physicians on the same practice site to address special health needs for patient with mental illness, proposed by other studies [36-38].

The United States may be facing a bigger challenge in this problem due to its high prevalence of mental illness. A recent study estimated that among adults aged 18-64, 21.9% had any mental illness, and 6.0% serious mental illness in the United States [15]. Those patients used to have no insurance, or at least lack of adequate insurance. Thanks to the Affordable Care Act (ACA), they are now not worrying about being denied health coverage by insurance companies due to their pre-existing mental conditions [39]. Also, they are entitled by the ACA to mental health services that were not covered by insurance before, even including preventive services [39]. Patient-centered Medical Home and Accountable Care Organization incorporates teamwork of health care professionals from a variety of specialties to achieve better coordination of care, which echoes the integrated health care model for mental illness treatment. We expect the mental condition-related disparities in preventable hospitalization and other health outcomes would significantly shrink if those innovative health care delivery models are implemented as planned.

Despite we used a longitudinal design to strengthen the establishment of causal relationship, there are some limitations in our study. First, we used Taiwan health insurance claims data, which lack of socioeconomic indicators, for example, educational attainment. We were only able to adjust for low-income status for multivariate analyses, but this panel data might mitigate this weakness. Second, we defined mental illness based on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes from the claims data, which may result in untreated patients being left out, so our estimations might be biased. Third, we did not have information on mental illness treatment in this study. It would be more meaningful to differentiate patients with the conditions under and out of control so that we could measure the effect of the treatment outcomes on preventable hospitalization among those patients.

Conclusion

Our study findings found that patients with mental illness are vulnerable to preventable hospitalization because of their lower socioeconomic status, medical condition and current non-customized health care delivery approach. It suggests that universal health coverage alone may not fully address the issue of preventable hospitalization among patients with mental illness, or even other special medical conditions. This highlights the importance of integrated health care delivery model with a multispecialty medical team. The United States could learn this lesson from Taiwan’s experiences as we are down the road to universal coverage required by the Affordable Care Act.

References

- Billings J, Anderson GM, Newman LS (1996) Recent Findings on Preventable Hospitalizations. Health Aff 15: 239-249.

- Magán P, Alberquilla A, Otero A, Ribera JM (2013) Hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions and quality of primary care: their relation with socioeconomic and health care variables in the Madrid regional health service (Spain). Med Care 49: 17-23.

- Agabiti N, Pirani M, Schifano P, Cesaroni G, Davoli M (2009) Income level and chronic ambulatory care sensitive conditions in adults: a multicity population-based study in Italy. BMC Public Health 9: 457.

- Agha MM, Glazier RH, Guttmann A (2007) Relationship Between Social Inequalities and Ambulatory Care-Sensitive Hospitalizations Persists for up to 9 Years among Children Born in a Major Canadian Urban Center. Ambul Pediatr 7: 258-262.

- Torio CM, Elixhauser A, Andrews RM (2013) Trends in Potentially Preventable Hospital Admissions among Adults and Children, 2005-2010: Statistical Brief #151.

- Jia H, Chuang H-C, Wu SS, Wang X, Chumbler NR (2009) Long-term effect of home telehealth services on preventable hospitalization use. J Rehabil Res Dev 46: 557-566.

- https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/InitiativetoReduceAvoidableHospitalizations/AvoidableHospitalizationsamongNursingFacilityResidents.html.

- Culler SD, Parchman ML, Przybylski M (1998) Factors related to potentially preventable hospitalizations among the elderly. Med Care 36: 804-817.

- Purdey S, Huntley A (2013) Predicting and preventing avoidable hospital admissions: a review. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 43: 340-344.

- Mai Q, Holman CDJ, Sanfilippo FM, Emery JD (2011) The impact of mental illness on potentially preventable hospitalisations: a population-based cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 11: 163.

- Gill J, Mainous AI (1998) The role of provider continuity in preventing hospitalizations. Arch Fam Med 7: 352-357.

- Tom JO, Tseng CW, Davis J, Solomon C, Zhou C, et al. (2010) Missed well-child care visits, low continuity of care, and risk of ambulatory care-sensitive hospitalizations in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 164: 1052-1058.

- Cheng SH, Chen CC, Hou YF (2010) A longitudinal examination of continuity of care and avoidable hospitalization: evidence from a universal coverage health care system. Arch Intern Med 170: 1671-1677.

- Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JPW, Strawderman RL, Weeks WB, et al. (2013) Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1879-1885.

- Walker ER, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Druss BG (2015) Insurance status, use of mental health services, and unmet need for mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv 66: 578-584.

- Cahoon EK, McGinty EE, Ford DE, Daumit GL (2013) Schizophrenia and potentially preventable hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 13: 37.

- Druss BG, Rask K, Katon WJ (2008) Major depression, depression treatment and quality of primary medical care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 30: 20-25.

- Fu TS, Lee CS, Gunnell D, Lee WC, Cheng AT (2013) Changing trends in the prevalence of common mental disorders in Taiwan: a 20-year repeated cross-sectional survey. Lancet 381: 235-241.

- Woodward M (1999) Epidemiology: Study Design and Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, Florida, USA.

- Jee SH, Cabana MD (2006) Indices for continuity of care: a systematic review of the literature. Med care Res Rev 63: 158-188.

- Saultz JW (2003) Defining and measuring interpersonal continuity of care. Ann Fam Med 1: 134-143.

- Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA (2004) Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo methods of comorbidity measurement in administrative data. Med Care 42: 355-360.

- Chien IC, Chou YJ, Lin CH, Bih SH, Chou P (2004) Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders Among National Health Insurance Enrollees in Taiwan. Psychiatr Serv 55: 691-697.

- Vissing NH, Jensen SM, Bisgaard H (2012) Validity of information on atopic disease and other illness in young children reported by parents in a prospective birth cohort study. BMC Med Res Methodol 12: 160.

- Menec VH, Sirski M, Attawar D, Katz A (2006) Does continuity of care with a family physician reduce hospitalizations among older adults? J Health Serv Res Policy 11: 196-201.

- Lin W, Huang IC, Wang SL, Yang MC, Yaung CL (2010) Continuity of diabetes care is associated with avoidable hospitalizations: evidence from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance scheme. Int J Qual Health Care 22: 3-8.

- Bentler SE, Morgan RO, Virnig BA, Wolinsky FD (2014) The association of longitudinal and interpersonal continuity of care with emergency department use, hospitalization, and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries. PLoS One 9: 115088.

- Lin IP, Wu SC, Huang ST (2015) Continuity of care and avoidable hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Am Board Fam Med 28: 222-230.

- Cahoon EK, McGinty EE, Ford DE, Daumit GL (2013) Schizophrenia and potentially preventable hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 13: 37.

- Li Y, Glance L, Cai X, Mukamel D (2008) Mental illness and hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive medical conditions. Med Care 46: 1249-1256.

- McGinty EE, Sridhara S (2014) Potentially preventable medical hospitalizations among Maryland residents with mental illness, 2005-2010. Psychiatr Serv 65: 951-953.

- Ajmera M, Wilkins T (2012) Multimorbidity, mental illness, and quality of care: Preventable hospitalizations among Medicare beneficiaries. Int J Family Med 2012: 823294.

- Kaufman EA, McDonell MG, Cristofalo MA, Ries RK (2012) Exploring barriers to primary care for patients with severe mental illness: frontline patient and provider accounts. Issues Ment Health Nurs 33: 172-180.

- Bauer MS, Williford WO, McBride L, McBride K, Shea NM (2015) Perceived barriers to health care access in a treated population. Int J Psychiatry Med 35: 13-26.

- Gehi A, Haas D, Pipkin S, Whooley M (2005) Depression and medication adherence in outpatients with coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. Arch Intern Med 165: 2508-2513.

- Lawrence D, Kisely S (2010) Inequalities in healthcare provision for people with severe mental illness. J Psychopharmacol 24: 61-68.

- Golomb BA, Pyne JM, Wright B, Jaworski B, Lohr JB, et al. (2000) The Role of Psychiatrists in Primary Care of Patients with Severe Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv 51: 766-773.

- Pirraglia PA, Kilbourne AM, Lai Z, Friedmann PD, O’Toole TP (2011) Colocated General Medical Care and Preventable Hospital Admissions for Veterans with Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv 62: 554-557.

- https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2013/08/21/affordable-care-act-and-expanding-mental-health-coverage.

Table A1: Multivariate-Adjusted Association Between Preventable Hospitalization and Continuity of Care (COCI in Continuous Form) from General Estimating Equation (GEE) Model, NHIRD 2006-2008.

* P<.05, ** P<.01, *** P<.001 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

LOGIN

LOGIN REGISTER

REGISTER.png)